The crisis has only just begun

by

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1)

June 9, 2020

How changes to work and housing set the tone of the struggle to come

inquiry

The crisis has only just begun

by

Callum Cant

/

June 9, 2020

How changes to work and housing set the tone of the struggle to come

Everyone knows that the crisis has only just begun. Porcine government ministers might talk about the peak of the pandemic like it’s long past. But for many workers, stuck at home contemplating the hard facts of rent and wages, the real peak is just appearing on their forward horizon.

I am not talking about a spike in the death rate (although there may well be another one of those before we’re done). Instead, I am talking about a peak in the capitalist crisis which this pandemic has catalysed. The sickly form of capitalism that emerged out of the crisis of 2008 always looked vulnerable, but none of us could have imagined the way it would be brought down: by a strange variety of capitalist crisis-via-lockdown. Britain, with a national economy whose non-financial capital is highly-reliant on service commodity production, will face a particularly virulent strain of this new threat.

In this article I want to discuss two onrushing factors that will shape the form of this crisis. By discussing them now, my hope is to contribute to a wider process of identifying how we, as a movement, can concentrate our efforts at key strategic points and create the conditions for working class resistance to the crisis to escalate from an immediate defence of material interests into a more fundamental class struggle over the future of society and the return to ‘normal’.

The first of these is the reopening of housing courts and the return to evictions. The second is the ending of the furlough and self-employed grant schemes. These two processes will transform the lives of millions of workers in the months to come, and so shape the battlefield on which the socialist movement will be forced to manoeuvre.

The return of evictions

As of this moment, the granting of possession orders by courts has been ‘stayed’, or paused. Whilst illegal evictions continue and many tenants leave their home before possession orders are granted due to a combination of fear and a misunderstanding of their legal protection, right now the majority of possible evictions will be on hold. This pause has occurred whilst huge numbers of tenants are unable to pay rent: 56% of residential rents went unpaid in April.

At first, this pause was only scheduled to last until the 25th of June. Late last week, however, it was extended to the end of August. Regardless of the exact date of this deadline, however, the outcome will be the same: as soon as the pause is over, the courts will start to grant possession orders once again and evictions will restart. The housing minister, Robert Jenrick, has indicated that he will write up a non-binding Pre-Action Protocol to try to persuade landlords to be nice, but it will have no legal status and probably have only a marginal impact upon their actual behaviour. Instead, it seems likely that a significant majority of landlords with tenants in rent arrears will begin the eviction process.

The UK currently sees around 120,000 possession orders granted per year. Given that the courts have stayed these proceedings for months, a backlog of tens of thousands of cases is likely to have built up. To this backlog will then be added all those caused by rent arrears during lockdown. Socially-distanced (and therefore less efficient) courts will have to try and process all of these cases as fast as possible when the stay ends, beginning with pre-lockdown possession orders and working forwards chronologically. The result is likely to be a wave of evictions on a scale which defies easy comparison. Should the pause be extended again, the same process would occur (potentially with an even greater volume of cases), just further down the line. Unless the government creates a legally-binding Pre-Action Protocol that forces landlords to accept either rent write-offs or repayment plans, the fundamentals of the situation will not change.

Homeowners also face a potential cliff edge. 1.8 million have taken advantage of a three month mortgage holiday scheme, with the window for applications now extended until the 31st of October. The ban on banks repossessing the homes of people who have fallen behind on their mortgages has also been extended to the end of October. An increase in the number of repossessions in autumn, whilst unlikely to be on the same scale as the wave of mass evictions discussed above, could add fuel to the potential fire.

The end of furlough

The UK private sector workforce is made up of 27.36 million people. Approximately 8.4 million of them are currently furloughed (as of May 10). The scaling down of this scheme is likely to shape the way that unemployment emerges during the coming recession.

Furlough closes to new employees from 10th June and begins to cost employers from August 1st. At first, they are liable only for National Insurance and pension contributions, and then more of the wage bill each month (10% in September, 20% in October) until the scheme ends at the start of November. As a result, employers who do not want to pay their furloughed workers are likely to start giving out redundancy notices over the coming months (the statutory minimum notice varies between one and twelve weeks depending on length of employment and can be modified by collective bargaining.) The 2.3 million people on the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme, many of whom are for all intents and purposes workers outside the employment relation, will also receive their final grant in August.

The number of claimants in receipt of UC rose 856,000 to 2.1 million in April (the biggest monthly rise since modern records began in 1971) suggests that workers made redundant during this time period will be joining an already very large pool of surplus labour. If even just 20 percent of these approximately 11 million state-supported people (the vast majority of whom will be workers) do not get reabsorbed into the workforce, the claimant rate would double. Ex-chancellors Hammond, Osbourne and Darling are already predicting up to 12% unemployment (c. 4 million workers). Perhaps the most damning evidence that this crisis is not just a future possibility but increasingly an existing reality is the fact that British foodbanks had their busiest month ever in April 2020, with usage rising by 89% compared to the year before.

Late last week, news emerged of a meeting between the Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Chancellor Rishi Sunak, and Business Secretary Alok Sharma in which the potential impacts of the economy remaining locked down over the summer were discussed. The prediction of 3.5 million jobs lost in the hospitality sector alone, particularly concentrated in the so-called ‘red wall’, so scared Johnson that the government has now pivoted to a much faster exit from lockdown in an attempt to ameliorate those symptoms of the crisis which might destabilise both their political control and the legitimacy of the mode of production more generally. BP’s announcement of 10,000 job losses (of which 2,000 are likely to be in the UK) is just the start.

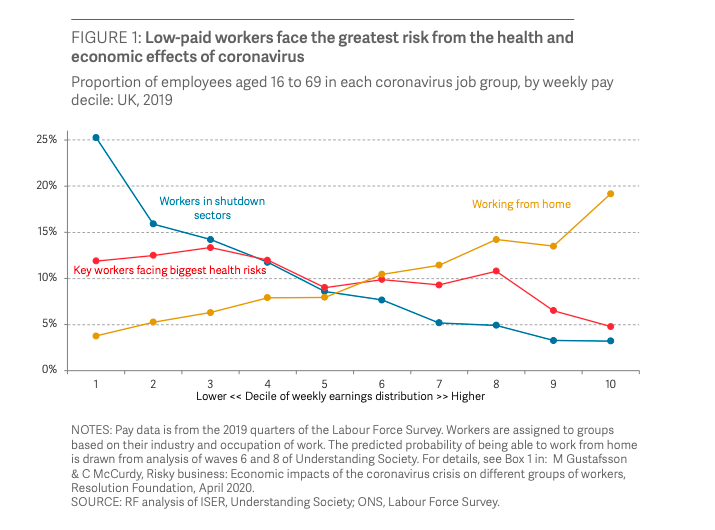

We already know, thanks to analysis by the Resolution foundation that Coronavirus has put both low paid workers both at the greatest risk of both infection and unemployment. It seems almost certain that the fallout from the crisis will hit the lowest earning deciles of the workforce hardest.

If the period after the crisis of 2008 saw low unemployment and falling wages, with most of the class experiencing the effects of it through a deterioration in their terms and conditions of employment and a collapse in public service provision, then this crisis will be profoundly different. For many workers, it will be marked by the experience of being thrown into the surplus population and forced into immiseration outside the wage.

Political implications and historical precedents

Our movement is not used to facing mass national unemployment. Whilst unemployment has always remained significant amongst certain regions and demographics, we have not seen numbers like 12% unemployment bandied about for decades. The challenge now facing us it to think through, in the few months we have left to prepare for this peak, how we can organise with workers who have been excluded from the workplace and whose struggles have moved from fighting over the immediate conditions of their employment as variable capital to struggles over access to the basic means of subsistence like housing and food.

Fortunately, we can draw on some analogies from Britain’s history. The National Unemployed Workers’ Movement (NUWM), founded in 1921, is probably one of the strongest examples of how unemployed workers can have a central role in the wider class struggle during periods of crisis.1 Established in 1921 under Communist leadership, the movement fought for the interests of the unemployed fraction of the class through direct and militant action until its dissolution in the late 30s. The testimony of activists from the movement is full of examples of such action. One activist from North Shields on Tyneside remembered the response of ghis local brand to an eviction in the early 1920s: ‘The family asked the NUWM for help. When the bailiffs arrived members of the NUWM were waiting. They told the bailiffs that if they went into the house their van would be turned over. The bailiffs left.’2 Other activities that made up the movement’s bread and butter included organising hunger marches, protesting local government, supporting strikes, representing the unemployed at benefit tribunals, and raiding workplaces where employers were using overtime rather than hiring more hands.

In a more contemporary context, the coming period is likely to bear some similarities to the Southern European experience of the post-Crisis period. In 2012, youth unemployment hit 50% in both Spain and Greece. In both cases, the result was the rapid development of social movements alongside a series of general strikes, followed by an uneasy process of relation to parliamentary politics through the vehicles of Podemos and Syriza. There is still much to learn from these experiences for the British left.

Come August this year, renters will no longer be protected from eviction. Unemployment is likely to further increase, with workers being made redundant as furlough is scaled back. The self-employed will lose government support, and homeowners will soon be vulnerable to banks repossessing their homes. Any one of these changes would be important on their own, but combined, they make the end of the summer look a lot like it’s going to be the real peak of this crisis.

The question of how socialists can prepare for this is a complex one. The rapid organic growth of an internationally-networked popular anti-racist movement looks like it will determine the political temperature for months to come. Relating to and supporting that movement whilst articulating Marxist analyses of systematic racism is a key priority. But in broader organisational terms, there are a few evident starting points at which we should focus our efforts. Renters’ unions like ACORN, Living Rent and the London Renters’ Union could play a significant role in the fight to come and need all the support the movement can give them. Where we are involved in mutual aid infrastructure, we need to start thinking about how these projects can be converted from dealing with self-isolation to supporting unemployed workers. In the workplace, coalitions need to be built between organised workers and their local communities in anticipation of potential battles against redundancies. One of the most effective tactics used against job losses historically has been the workplace occupation. Where possible, further uses of this tactic could offer us leverage in difficult situations.

Footage from the Vestas wind turbine factory occupation on the Isle of Wight in 2009

In political terms, there are a few demands we can make against the state on the specific questions of work and housing: protect employment through the expansion of public ownership under workers’ control and a massive public works scheme based on a Green New Deal; provide guaranteed access to the things we need to live like food and housing; and enforce a legally-binding national rent and mortgage write-off.

Above all, we have to be clear that the way out of this crisis is not through a return to a ‘functional’ capitalist economy. Such functioning is, in and of itself, predicated on the domination of the vast majority of humanity by a ruling class of bosses and owners. We have no desire to return to normal. Only through the struggle of a socialist movement based in the working class can we begin to see beyond the peaks and valleys of our historical moment, and towards a new, red horizon.

author

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

It's time to close our schools

March 16, 2020