The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project

by

Erin McElroy,

Manon Vergerio,

Sam Raby

October 9, 2019

Featured in Housing (#10)

Counter-mapping Evictions in the San Francisco Bay Area and New York City

inquiry

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project

Counter-mapping Evictions in the San Francisco Bay Area and New York City

The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP) is a counter-cartography, data visualization, and multimedia storytelling collective that emerged in the San Francisco Bay Area in order to provide maps, data, tools, and stories to empower on the ground anti-gentrification organizing. The project has since grown to develop chapters in Los Angeles and New York City and ongoing solidarities with mapping collectives and anti-eviction organizations worldwide. While AEMP project members have written about the collective in a variety of sources, many of which can be found on our website, here we will explain a bit of the project’s genesis in the Bay Area, how we went about forming a new chapter in New York, and why we find it imperative to ground our mapping and analysis in anti-racist, anti-capitalist, and decolonial frameworks. We end by describing some of our newest work and upcoming projects. In doing so, we consider community-driven map-making a form of inquiry that allows us to collectively produce spatial knowledge useful in housing justice struggles.

Bay Area Emergence

The AEMP emerged in San Francisco during the dawn of the Tech Boom 2.0, or the Second Dot Com Boom, the period following both the late 1990s Dot Com Boom and the 2008 foreclosure crisis. Of course, these eras rest upon those of times past, from the Gold Rush and the dawn of settler colonialism to mid-twentieth century cartographic projects of redlining. They include the redevelopment and urban renewal projects that decimated San Francisco’s Black communities to the Cold War. They are rooted in the government R&D funding that in many ways solidified Silicon Valley and the Bay Area as hubs of imperial technology. These are all times that endure and inform the present. During the Boom Tech 2.0, real estate speculation and technocapitalism began to entangle in novel ways, updating the racial dispossession of prior times in the forms of eviction, rent increase, digital surveillance, income inequality, and housing precarity. While the AEMP emerged during this context, it grew out of and was from its earliest moments supported by the San Francisco Tenants Union, a tenant-led organization that has been fighting for housing justice since 1971. In this way, anti-eviction organizing of the present rests upon a _longue durée _ of tenant justice work and knowledge generation.

The AEMP emerged alongside the direct-action collective, Eviction Free San Francisco (EFSF). Both groups consolidated in order to provide data and organizing work outside of the nonprofit and for-profit housing landscapes. While EFSF held biweekly meetings in which tenants facing eviction could be supported in direct action work, the AEMP labored more behind the scenes, mapping evictions, analyzing trends, and researching the webs of shell companies being used by corporate landlords in order to maintain anonymity and financial gain. Our earliest map detailed the accumulation of evictions under the state Ellis Act over time in San Francisco. Ellis Act evictions are a type of no-fault eviction disproportionately used by real estate speculators in California in order to evict rent-controlled tenants “for no fault of their own” and flip the units into condos, amassing huge profits. The Ellis Act, along with the Costa-Hawkins Act, passed a decade later, are statewide landlord laws written to maintain real estate power. In addition to weakening rent control laws in cities such as San Francisco, Oakland, Santa Monica, Los Angeles, and Berkeley, the Costa-Hawkins Act in particular makes it much more difficult to pass rent control in cities without protections—the majority of cities in California.

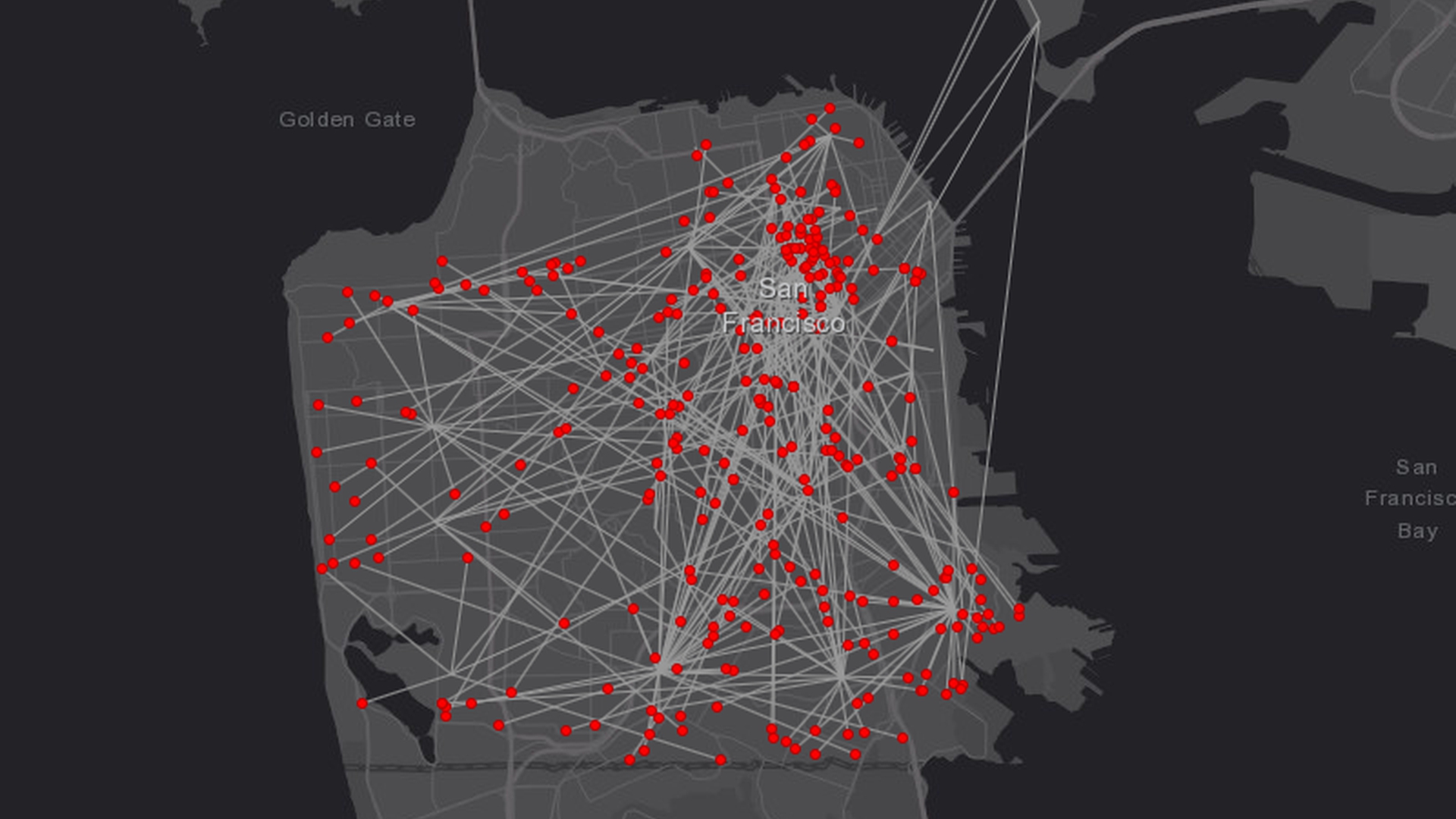

Our first map detailed the accumulation of Ellis Act evictions from 1994 to the present in San Francisco, detailing where evictions transpire and who the evictors are. The landlord-sponsored Ellis Act was penned in 1985 in Sacramento following successful rent control campaigns throughout the state, with the aim of weakening rent control protections. Soon after our first map appeared on line, sidewalk stencils with the words, “Tenants Here Forced Out,” were crafted, and people began spray-painting the sidewalks in front of evicted properties, bringing what had been a digital web map into analog space to disrupt the housing market. We were also able to craft a look-up tool, so that tenants could look up addresses and determine if they have eviction histories, and if so, pledge not to rent or buy from them. Since then, we have continued to entangle analogue and digital mapping work, from mural work to light projections, from report writing and zine production to the coproduction of community events.

From its inception, the AEMP has worked alongside an array of community partners. Some of the project’s earliest research was conducted with the statewide tenant organization Tenants Together in order to help analyze Ellis Act evictions, Costa-Hawkins impacts, and the speculators who rely upon them which we released as co-producing reports and analyses used in policy reform. For instance, we found that 60 percent of Ellis Act evictions in San Francisco occur within the first year of ownership, and that 80 percent transpire within the first five. This indicates that Ellis Act evictions are not being issued by long-term mom and pop landlords (a real estate industry myth), but rather by those who speculate upon the market value of a building once vacated of rent-controlled tenants. This data has been instrumental in pushing for Ellis Act reform on statewide and local levels. In this way, while on the one hand we conduct research to embolden direct actions and groups working against real estate speculators outside of the policy and nonprofit world, on the other, we also strategically partner with policy groups and organizations. As such, we understand that policy reform, while not always as revolutionary as we wish for, nevertheless is a means of harm reduction with the material power to keep tenants housed.

We’ve also annually collaborated with the Eviction Defense Collaborative in San Francisco to analyze client data. We have found that on average Black tenants are overrepresented by 300 percent amongst those formally evicted in the city. We also were able to map where tenants end up following eviction, charting not the transient desires of real estate speculation but rather the undesired forced mobilities that tenants of color disproportionately endure.

When the AEMP emerged, we initially wanted to produce maps and analysis in both San Francisco and Oakland, as the members of our volunteer-led collective lived and worked in both. However, we had a much more difficult time accessing data in Oakland than in San Francisco. Yet over time, we began to make headway in terms of obtaining Oakland eviction data from the Oakland Rent Board and the Alameda County courts, again in partnership with Tenants Together and a number of other East Bay community partners. Much of this was published in the form of a 2016 collaborative report, entitled Counterpoints: Bay Area Data and Stories for Resisting Displacement. Also included in this report was our first ever community power map, in which we were challenged by one of our community partners, the black-owned feminist Betti Ono Gallery, to consider not only spaces of loss and displacement, but also community assets, sites of refusal, and joy. This collaboration challenged us to refrain from more normative social scientific projects of mapping loss and dispossession in a way that produces autopsies of already racially dispossessed spaces and people.1 As we were challenged to think, what would it mean to map geographies of community power in order to signal futures beyond those of dispossession?

Counterpoints also contained an array of oral histories and video pieces, building upon ongoing narrative work that we had been conducting as a project since 2014. It was then, only a year into the project’s inception, that we began to realize that our quantitatively driven analyses, while important, were also rendering complex life stories and neighborhood histories to simple dots on maps, or abstract choropleths on flattened topographic renditions. We thus launched an oral history and video project entitled Narratives of Displacement and Resistance, which we released alongside our first mural and zine, all of which contained personal stories of loss and resistance, geolocated upon a sea of less detailed eviction data.2 While this early narrative work was just San Francisco focused, we have now produced oral histories and video work throughout the region, and now, more recently also in our new New York City and Los Angeles chapters.

New York City

The New York City AEMP chapter was established in August 2017 by a small group of founding members, including a few who had been members of AEMP in San Francisco. Tapping into the methodologies and collective knowledge developed in San Francisco, while recognizing the need to develop a practice specific to the New York City context, we spent the first year focusing on relationship-building with tenant organizing groups, housing data activists, oral historians, and anti-displacement collectives. To find our place within an ecosystem much larger and more decentralized than San Francisco, we prioritized skill-sharing with other activist groups, lifting up and celebrating existing oral history projects around gentrification and displacement, and engaging in exploratory conversations within the housing movement to learn how we could support ongoing campaigns. Following this collaborative ethos, we organized a skill-share with the Equality for Flatbush Real Estate Watch Team to share strategies for conducting research on predatory landlords in January 2018 and a community Oral History 101 Workshop at Picture the Homeless in May 2019. In addition, we invited oral historians to contribute stories they had recorded in their communities to our public online platform Narratives of Displacement and Resistance, which now features stories from Cities for People, Not For Profit in Bushwick and the Mott Haven Oral History Project in the South Bronx.

Following our longstanding commitment to document and organize against evictions, we developed a deep collaborative relationship with the Right to Counsel (RTC) coalition and JustFix.nyc, enabling us to develop the Worst Evictors project. Combining the research and knowledge of tenant organizers from the RTC coalition, data analysis from JustFix.nyc, and interactive map development from AEMP, the Worst Evictors platform publicly shames serial evictors and strives to shift the narrative around evictions in NYC.

A key organizing goal of the Worst Evictors project was to highlight Right to Counsel, a NYC law that grants free legal representation to tenants facing eviction. Although only implemented in select neighborhoods around the city, the law has proven to be highly effective in preventing displacement. The project identified landlords with the most evictions in areas where the Right to Counsel law was currently in effect—to call attention to the law and galvanize folks who currently have this right to fight back—while also connecting these individual evictors to the larger systemic crisis through the citywide evictions map. Since the eviction records that NYC provides (by open data law) are virtually unusable for analysis, the eviction data we used for the Worst Evictors project relied on months of volunteer labor from the Housing Data Coalition and AEMP members to sanitize, deduplicate, and geocode the raw City data. Given this work, a report from Gothamist called the project “the most comprehensive database yet to measure evictions across New York City and identify many of the landlords responsible for them.”

Landlords, the real estate industry, and the City tend to portray evictions as an individual problem caused by “bad tenants.” Our collective aspiration was to shift public opinion to recognize evictions as part of a corporate business tactic, where profit is extracted by dispossessing New Yorkers of their homes and communities. To launch the Worst Evictors project, we participated in a Week of Action where we supported RTC NYC coalition members to call out some of the worst evictors across the city, staging actions at housing courts and corporate landlord offices across four boroughs. We were honored to stand in solidarity with tenants in Brooklyn, Manhattan, the Bronx and Queens in their fight for housing justice.

Mapping Racial Capitalism

While much scholarship and thinking on gentrification foregrounds capitalism as the incendiary force behind dispossession, we align our project with work that positions capitalism as always entangled in racism. In this way, we find it imperative to center the analysis of what scholars such as Cedric Robinson describes as “racial capitalism.” This is the notion that from its earliest Western European origins, capitalism inhered racism and raciality.3 In other words, all capitalism is racial capitalism. We belabor this point here in this Notes From Below special issue on housing as we find it important to not make a deracinated analysis of capitalism in understanding possession and dispossession. Put otherwise, it is impossible to map displacement from the ground up without attending to the longstanding entanglements capital concretizes with race. As Jodi Melamed writes, “Capital can only be capital when it is accumulating, and it can only accumulate by producing and moving through relations of severe inequality among human groups—capitalists with the means of production/workers without the means of subsistence, creditors/debtors, conquerors of land made property/the dispossessed and removed. These antinomies of accumulation require loss, disposability, and the unequal differentiation of human value—racism enshrines the inequalities that capitalism requires.”4 In this way, capitalist accumulation reproduces racial dispossession.

From the first settler colonial projects that decimated Indigenous Ohlone life in the Bay Area to projects of redlining, redevelopment, white flight suburbanization, the foreclosure crisis, to Dot Com Boom and Tech Boom 2.0 speculation, raciality has always informed cycles of dispossession.5 While settler colonialism and racism are continually updated in each of these phases, we would be remiss to not note how often these updates often rely upon mapping and data accumulation, from those of the earliest settler topographic technologies to those of real estate speculative maps of today. In this way, we find it important to frame our own mapping and data work in the tradition of critical and feminist cartography, decolonial methods, and data justice work.6

As our work extends to new cities, we believe it is crucial to ground the framework of racial capitalism in the situated contexts in which we organize. The historical trajectory and material landscape of New York City, in particular, have been shaped by the interlocking systems of race and capitalism from the day of its founding by Dutch settlers on Lenape land. This initial land grab, financed by imperialism and predicated on the dispossession of Indigenous peoples, ushered in a perpetual cycle of settlement and displacement.7 Deeply intertwined with the history of finance and property in NYC is that of slavery as well, which allowed the city’s financial elite to consolidate their power and wealth through the exploitation of black bodies.8 Over time, racial inequality and segregation have been carved out by discriminatory federal programs and market forces, and reinforced at the city-level by decades of racialized housing policies, zoning, and land use regulations.9

Today, New York City continues to rely heavily on zoning as its primary mechanism for city planning, an urban planning technique often presented as efficient, rational, and colorblind. Yet, critical geographers Bobby Wilson and Sam Stein argue that zoning acts as “a tool to accommodate the racial order,”10 and has been repeatedly weaponized “to target one racial group for exclusion or expulsion while clearing the way for another’s quality of life” (ibid: 28). Under the current administration of Mayor De Blasio, neighborhoods of color across the city are systematically targeted for rezonings that turn these working-class areas into terrains for speculation and high-rise residential development overnight while increasing displacement pressures on long-term residents. We believe it is crucial to recognize how current city planning policies embody ongoing processes of racialized accumulation by dispossession and the need to maintain an intersectional lens of gentrification as a deliberate restructuring of cities along class and racial lines.

Future Work

Our forthcoming work in both the San Francisco Bay Area and New York City aims to center our antiracist and decolonial politics in our approaches to cartography in order to produce data and maps useful to movement building and knowledge production. For instance, the Bay Area chapter is currently in the midst of producing our first atlas, Counterpoints: A San Francisco Bay Area of Displacement and Resistance, as well as our zine, Black Exodus/Dislocations. Both text pieces take a historical approach to mapping displacement of the present. Our atlas, which will be published by PM Press in 2020, is comprised of seven chapters, each edited by a different AEMP editorial team, and encompass the following themes: Evictions and Root Shock; Indigenous Geographies; Environmental Justice and Environmental Racism; State Violence and Gentrification; Transportation and Infrastructure; Migrations and Relocation; and Speculation and Speculative Futures. Each chapter offers historic context in order to map and understand the present, and incorporates new mapping work made by the AEMP as well as a new series of community partners and contributors.

Meanwhile, Black Exodus/Dislocations came out in August 2019, and incorporates new narrative work, maps, art, and analyses made with a series of San Francisco community partners in order to tell the story of Black displacement of the past and present. Some of this work overlaps with a new film that we are in the midst of producing with the Regional Tenant Organizing network (RTO), detailing contemporary anti-gentrification struggles. These, respectively, narrate the contemporary eviction struggle and fight of former Black Panther, Aunti Frances, in Oakland, the fight against Google’s new campus in San Jose, and the ongoing fight for rent control in Santa Rosa.

Amidst this new narrative and text-based work, the AEMP project has also been in the midst of a data and website redesign project to create better infrastructure for our project growth. We recently added new filter and search features on our website so that our work can be searched thematically and/or by location. Since summer 2019, we have been working on the creation of a new database structure and look-up tool so that our various data sets can better exist in relationship in order for users to better understand the connections between addresses, evictions, property ownership, and real estate speculators/LLCs. Work on this tool has brought together members of all three AEMP chapters, as well as our collaborators in Portland, the Mapping Action Collective.

Meanwhile, the NYC AEMP chapter is looking forward to continuing our work in solidarity with the Right to Counsel (RTC) coalition in their fight against evictions. We plan on recording oral histories with RTC members over the summer to add a personal, narrative-based dimension to our citywide map of evictions that not only records losses, but also resistance and organizing strategies. We hope to then extend this narrative work beyond the RTC coalition by hosting oral history recording sessions in community spaces across the five boroughs. In October 2019, we will be collaborating with RTC and the International Alliance of Inhabitants to organize an International Evictions Tribunal to put some of the worst evictors in the city on trial through a people’s tribunal.

In the spirit of making our work accessible not only online but offline as well, we are working towards organizing a joint listening party with Cities for People, Not For Profit to provide a collective space to listen to and analyze oral histories from our movement as both a tool for political education and recruitment. Additionally, we will also be presenting our mapping and narrative work at the Mapping (In)Justice Symposium at Fordham University in November 2019.

All of these past and future projects center collaborations between the AEMP and its various community partners, endeavoring not to step on the toes of existing work, but rather to support ongoing housing justice efforts. We consider our volunteer-led labor of mapping, storytelling, and collaborating one of many cogs within a broader housing justice movement. Maps are, after all, able to tell an infinite amount of stories, and are frequently employed by real estate speculators to perpetuate the projects of settler colonialism and racial capitalism. Yet by considering cartography and housing justice as interconnected fields of inquiry, we are able to push for cartographic and housing justice futures beyond geographies of dispossession.

-

Erin McElroy and Alex Werth. 2019. Deracinated Dispossessions: On the Foreclosures of ‘Gentrification’ in Oakland, CA. Antipode, 51(3): 878–898. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12528 ↩

-

Manissa M. Maharawal and Erin McElroy. 2018. The Anti-Eviction Mapping Project: Counter Mapping and Oral History toward Bay Area Housing Justice. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(2): 380–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1365583 ↩

-

Cedric Robinson. 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill. ↩

-

Jodi Melamed. 2015. Racial Capitalism. Critical Ethnic Studies, 1(1), p. 77. ↩

-

Ananya Roy. 2019. Racial Banishment. Keywords in Radical Geography: Antipode at 50. Edited by Tariq Jazeel et al. Hoboken, NJ: Antipode Foundation: 227–230; Ariana Faye Allensworth, Adrienne Hall, and Erin McElroy. 2019. (Dis)location/Black Exodus and the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project. Radical History Review: Abusable Past. https://www.radicalhistoryreview.org/abusablepast/?p=3191. ↩

-

Sarah Elwood and Agnieszka Leszczynski. 2018. Feminist Digital Geographies. Gender, Place & Culture, 25(5), 629–644. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1465396; Andy Kent et al. 2017. Symposium – The Detroit Geographical Expedition and Institute Then and Now. AntipodeFoundation.org. https://antipodefoundation.org/2017/02/23/dgei-field-notes; Desiree Rodriguez-Lonebear. 2016. Building a Data Revolution in Indian Country. Indigenous Data Sovereignty, p. 253, 10.22459/CAEPR38.11.2016.14. ↩

-

Tom Angotti. 2008. New York For Sale: Community Planning Confronts Global Real Estate. MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, p. 43. ↩

-

Angotti, p. 58. ↩

-

Tom Angotti and Sylvia Morse (Eds). 2017. Zoned Out! Race, Displacement, and City Planning in New York City. Terreform: New York, p. 47. ↩

-

Sam Stein. 2019. Capital City: The Rise of the Real Estate State. Verso Books: New York, p. 21. ↩

Featured in Housing (#10)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Gimme A Home...

by

Chris Carlsson

/

Oct. 9, 2019