The Workers’ Inquiry and Social Composition

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

January 29, 2018

Featured in No Politics Without Inquiry! (#1)

A new framework for class composition analysis

theory

The Workers’ Inquiry and Social Composition

by

Notes from Below

/

Jan. 29, 2018

in

No Politics Without Inquiry!

(#1)

A new framework for class composition analysis

This piece was written to outline our position on workers’ inquiry in the Notes from Below project. It is intended to update and refresh the approach through the explicit integration of ‘social composition’, put forward by Seth Wheeler & Jessica Thorne. We have collectively developed this in the piece that follows, structured into four arguments.

1: Why Workers’ Inquiry?

Workers’ inquiry is an approach that combines knowledge production with organising. It attempts to create useful knowledge about work, exploitation, class relations, and capitalism from the perspective of workers themselves. There are two forms of workers’ inquiry. The first is inquiry ‘from above’, involving the use of traditional research methods to gain access to the workplace. The second is inquiry ‘from below’, a method that involves ‘co-research’, in which workers themselves are involved in leading the production of knowledge. If the conditions exist, the inquiry ‘from below’ is clearly favourable. The knowledge that is produced from either of these forms of inquiry is useful for understanding capitalism, but also for organising against it.

This is why Notes from Below platforms the voices and experiences of workers in their fight against capitalist exploitation. We want to ground our politics in the perspective of the working class, help circulate and develop struggles, and build workers’ confidence to take action by and for themselves.

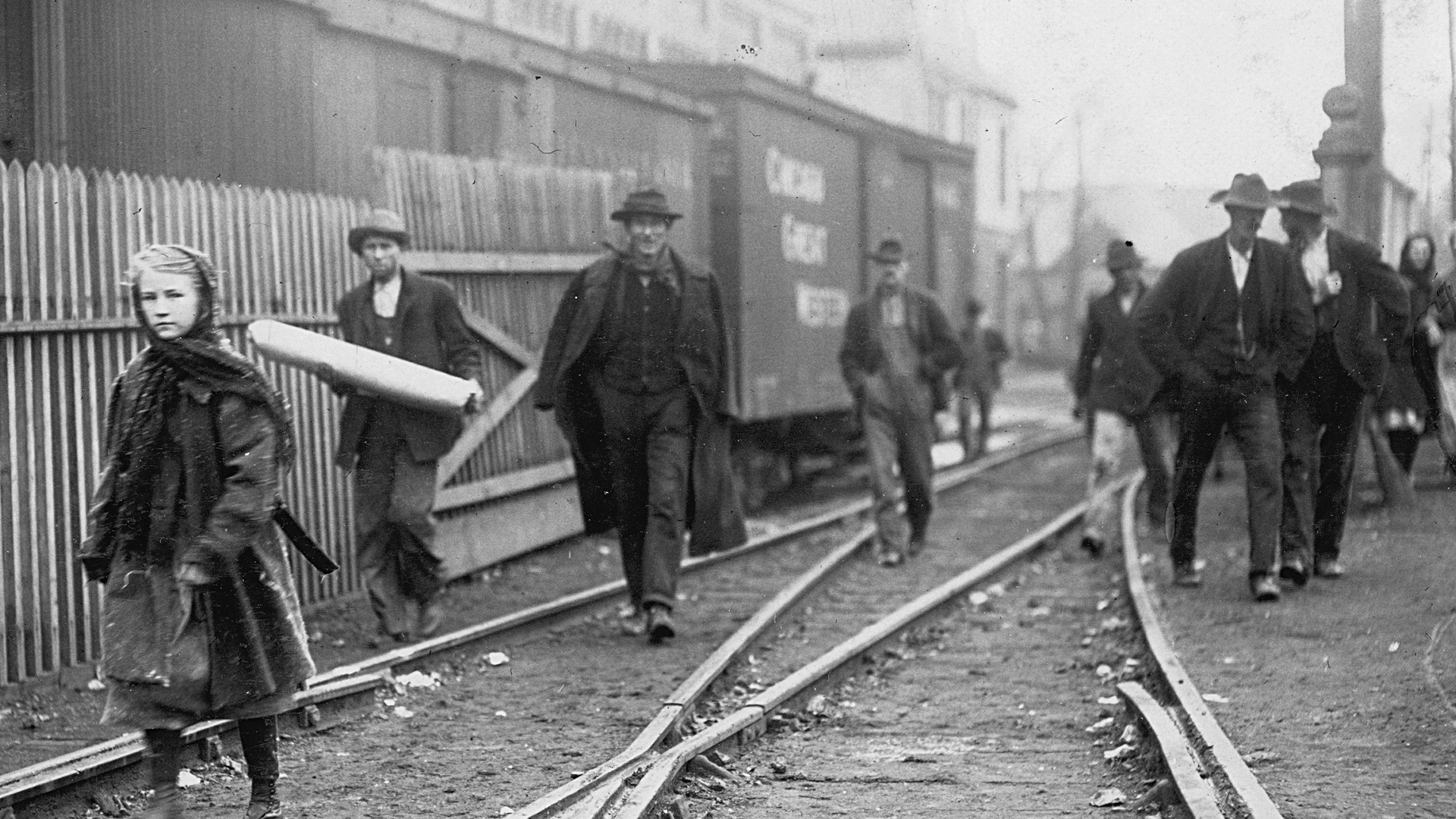

There are two reasons why we focus on work. First, it is central to the working class perspective. From the perspective of a individual worker, it is difficult to see how their own work recreates capitalism every day. But workers know intuitively that if the working class stopped working, everything would shut down. Collectively, workers perform vital functions at different points of production and circulation. Through this position the working class can develop a unique viewpoint. This perspective shows the direct experience of capitalist exploitation, while also pointing towards the kinds of struggle that can destroy it. A successful revolution has to begin from below.

Second, capitalism is totally reliant upon work. Without work, there is no new value produced, and no capitalist mode of production. The relationship between classes expressed at work is fundamental to understanding society. But understanding capitalism demands more than an understanding of class relations. Work is the only relationship in which the workers produce surplus value, but it is not the only one in which people experience oppression. We need to analyse all aspects of working class life. However, we think that abandoning work as the primary site of struggle is a mistake. As a result, we are proposing a correction: a return to resisting, analysing, and organising at work. This is not in opposition to other projects, but renewed and reinvigorated by new experiences. Workers’ inquiry is the method that can start doing this in practice. It begins from the actual experience of capitalist exploitation.

2: Why Class Composition?

Capitalist exploitation is not an abstract idea; it always takes particular, material forms. Through class struggle, capitalism changes itself. This creates new technologies and work processes. It involves the movement of people and capital to new parts of the world, developing new industries. The terrain of class struggle changes, along with the working class itself. We need to analyse this terrain, to find out where capital is weak and where workers are strong. Where are our forces? How do we attack? The only way to find out is within the class struggle itself. Therefore, workers’ inquiry does not just uncover the changing forms of work, but the changing forms of struggle.

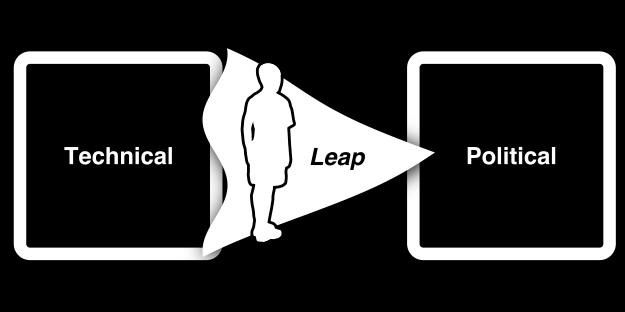

The Italian workerists had a phrase for this changing aspect of work and struggle: the ‘class composition’. They divided class composition into two parts. The first is ‘technical composition’. This is the specific material organisation of labour-power into a working class through the social relations of work. It is shaped by factors like the use of technology, management techniques, and the overall design of the labour process. The second is ‘political composition’, which follows from technical composition. It is the self-organisation of the working class into a force for class struggle. This includes factors like the tactics employed by worker resistance, forms of worker organisation, and the expression of class struggle in politics. Technical composition sets the basis for political composition, although the movement from one to the other is not mechanical or predictable. Instead, it is an internal development and political growth which leads to a leap forwards. This leap ultimately defines the working class political viewpoint.

Class composition provides a framework for the analysis of the results of workers’ inquiry. Through it we can examine the content of work and connect this to resistance. This involves focusing on the labour process and what Marx called ‘the hidden abode of production.’ Marx is talking here about the workplace. Most of the time we cannot see what is happening behind these closed doors. Workers’ inquiry provides a way into this ‘hidden abode’, behind which Marx argues, ‘we shall see, not only how capital produces, but how capital is produced. We shall at last force the secret of profit making.’ The secret that Marx reveals in Capital is that labour produces surplus value under capitalism. Class composition analysis reveals another secret: how workers turn themselves into a political force.

Marx stresses the importance of the labour process and it is useful to return to his definition: ‘the elementary factors of the labour-process are 1, the personal activity . . . i.e., work itself, 2, the subject of that work, and 3, its instruments’. To this we can add different relations to the wage-form, work, other workers, means of production, and product. (See Kolinko for a breakdown of these different elements). Through these categories, we can differentiate between types of work and how they are organised. This is the basis of technical composition.

Too often, analysis of work focuses on the details of work and not the experience of workers. That experience is not a mystery, all workers experience this every day. A class composition analysis starts from the technical composition, but does not remain there. Our goal is not to understand work, but to inform the struggle against it. Hence the need for a move into the analysis of political composition.

3: Why “Social” Composition?

We do not just want to apply the concepts of Italian workerism again today. It provides an important inspiration and a powerful set of tools, but to use these effectively they also need to be updated. We believe, like Battaggia , that ‘the best way to defend workerism today is to supercede it.’ An update to class composition is necessary. Our suggestions aim to build on its strengths, but also seek to move it forward.

In particular, we feel that previous analysis of class composition has based workers and their resistance almost exclusively on the workplace. Yet workers are made into a class before they are employed by a capitalist. Before they are required to sell their time, they are dispossessed of the means of production. Tied to this condition is a whole range of political struggles beyond the wage. This includes those over the conditions of state-provided social services, migration and borders, housing and rent, and a wide range of other issues. We believe that analyses of technical composition alone can produce their own hidden abodes beyond work. We therefore propose a third dimension: social composition.

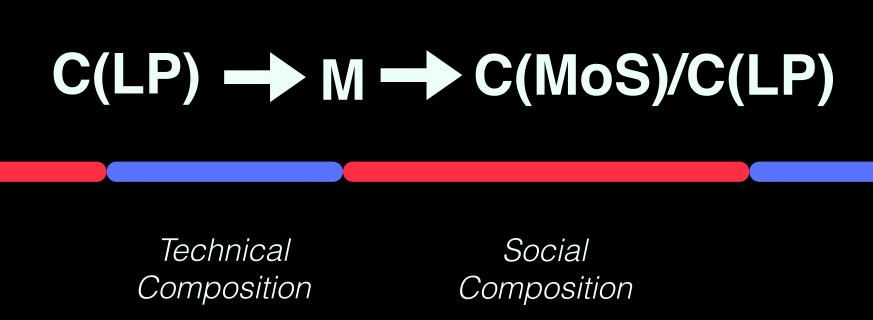

To explain this, we need to return briefly to Marx. Marx defines capital as money that makes more money. This is expressed in the formula Money-Commodity-Money (M-C-M), or buying in order to sell. Under capitalism, this involves an increase in the quantity of value through the addition of surplus value. This surplus is created through the exploitation of labour-power at work. So, Marx proposes M-C-M¹ as the general formula of capital . This is how Marx prepares for his analysis of the ‘hidden abode of production’, and where the technical composition of the working class is to be uncovered.

Yet Marx also proposes another form of commodity circulation: selling in order to buy. This circuit has the formula Commodity-Money-Commodity (C-M-C). The working class (who have no commodity to sell but their own labour-power) sell their time for a wage, which they use to buy the commodities they need and desire in order to live.

So if M-C-M¹ is the general formula of capital, what is C-M-C? It is the general formula of working class reproduction. The working class sell their labour power in exchange for a wage through the process of work. They then exchange this wage for the commodities necessary for them to reproduce their labour power, otherwise known as the means of subsistence. These commodities are transformed back into labour power – and then the whole cycle begins again.

The commodity form is dominant in capitalist society. We can use the form of its circulation within this general formula of working class reproduction to map the social relations of workers beyond work. However, as things stand, class composition analysis cannot understand workers beyond work.

When workers are recovering from the experience of work they are a mystery. Having escaped their technical composition, they only factor into class composition analysis if they decide to act politically, rather than shopping, eating, relaxing, or sleeping. These activities of reproduction are only understood from the perspective of those producing them, or from the moment the reproduced worker starts the next shift. We believe that it is possible to update class composition to account for reproduction. We will do so through the concept of social composition.

Social composition combines with technical composition before the leap into political composition. Social composition is the specific material organisation of workers into a class society through the social relations of consumption and reproduction. This general formula of working class reproduction allows us to understand the boundaries between forms of composition.

Social composition is primarily a way to understand how consumption and reproduction form part of the material basis of political class composition. It involves factors like: where workers live and in what kind of housing, the gendered division of labour, patterns of migration, racism, community infrastructure, and so on.

Workerism mainly dealt with workers in commodity production whose labour-power was exploited for surplus-value. Social composition allows us to extend the logic of class composition analysis to the whole of the working class. This includes the unemployed and workers not directly involved in producing the capitalist form of value. Both productive and unproductive workers are members of the same class. They all lack control of the means of production, sell their labour-power to survive, and work to reproduce capitalist society. Class composition is grounded in the working class viewpoint on work, not on capital’s viewpoint of productivity.

4: Why does this matter?

Our version of class composition understands the leap into political composition from both a technical and social basis. Class struggle at work emerges from the entirety of working class life. This updated framework takes into account these factors.

Class composition is a material relation with three parts: the first is the organisation of labour-power into a working class (technical composition); the second is the organisation of the working class into a class society (social composition); the third is the self-organisation of the working class into a force for class struggle (political composition).

In all three parts, class composition is both product and producer of struggle over the social relations of the capitalist mode of production. The transition between technical/social and political composition occurs as a leap that defines the working class political viewpoint.

We intended to test and refine our new framework for class composition in Notes from Below. This has to begin, as Marx argued, from an exact and positive knowledge of the conditions in which the working class – the class to whom the future belongs – works and moves. Such knowledge provides the only viable basis for a development of class struggle towards more developed forms of self-organisation. As Ed Emery put it: no politics without inquiry!

Featured in No Politics Without Inquiry! (#1)

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next