Labour Rights in Esports

by

Marijam Didžgalvytė (@marijamdid)

March 30, 2018

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

The esports industry is a multi-billion dollar industry that treats its competitors poorly, but the tide is starting to change.

inquiry

Labour Rights in Esports

by

Marijam Didžgalvytė

/

March 30, 2018

in

Technology and The Worker

(#2)

The esports industry is a multi-billion dollar industry that treats its competitors poorly, but the tide is starting to change.

Tech workers are unionising, games industry staff are unionising, and the workers manufacturing our electronic goods in China are striking back. In this new realm of jobs, it is the electronic sports (esports) competitors who are severely lagging in understanding their value in profit creation. While famous figures such as Shaquille O’Neil, Jennifer Lopez, Ashton Kutcher and others are investing vast sums of money into the competitive gaming realm, the workers of this field, players themselves, are living the opposite of a glamorous lifestyle. Many report terrible training conditions, underpaid salaries, and terminated contracts as common practice. With no professional structures in place, complaining about one’s position in a traditional way is troublesome— blacklisting is prominent and no trade unions are there to help. This tide is changing, however, with a few industry veterans beginning to recognise a need for a professional esports association that would solidify the competitors’ workplace rights.

The historical context

Electronic sports have existed since young people started competing for a penny or two at their local arcades. The autumn of 1980 saw the earliest large-scale video game competition when Atari’s Space Invaders Championship attracted more than 10,000 participants in Warner’s New York headquarters. By the 1990s, esports competitors were earning huge tournament wins while playing titles such as Quake, Counter-Strike, and World of Warcraft. However, it was the explosion of competitive gaming in South Korea in the early 2000s that really established esports as the entertainment juggernaut it is today. Top-tier Korean ‘League Of Legends’ or ‘Starcraft’ players are treated as national treasures who deserve their seven-figure-plus salaries. On the other hand, for every success story, there are thousands of teenagers who have dropped out of school to become professional esports competitors, only to be quickly disillusioned by the long hours, restrictive contracts, and poor benefits.

With some tournament prize pools now reaching over $20 million dollars, one can understand why it is such an appealing career prospect for young people around the world. And yet, for all its success, the esports sector in the Global North still lacks a trade union equivalent to Professional Footballers Association (PFA) in order to defend their talent from money-grabbing, abusive managers, and shady leagues. Due to the sheer size of the industry, South Korea did establish The Korea Esports Association (KeSPA) in 2000, but it has since been discredited by accusations of match-fixing and embezzlement.

The current situation

The most recent wave of support towards the unionisation of esports competitors came in December 2016 when the godfather of the US CS:GO scene, SirScoots (real name Scott Smith), posted a public letter calling out the Professional Esports Association1 for preventing some of the best CS:GO teams from competing in the ESL Pro League (EPL). The letter, posted on behalf of several different CS:GO teams, explained the significance of such a limitation:

In a profession where so much of your income depends on your performance and brand exposure, being able to choose where you play is vital.

The negative consequences of playing exclusively in one league have already been exposed in the past — 2007 saw The Championship Gaming Series (CGS) create a monopoly in the CS community. The players were expected to toss out positive mentions of the CGS in any media appearances, were not allowed to attend smaller, local tournaments, and were forced to play versions of the game that would prove to be obsolete after the contract had ended. Even worse, after the league inevitably flopped due to poor business management, it had already ousted many smaller organisations, leaving many of the players unemployed for years to come.

The purpose of the the players’ letter to the PEA, published on 22 December, was that ‘’by involving the community in this discussion, an example can be set for the kind of respectful, open, transparent dialogue that should be the industry standard.’’ Unfortunately, quite the opposite was the result — one of the 25 signatories of the letter, Sean Gares, was singled out, contacted by the heads of the PEA and ultimately sacked from the team by the founder Andy Dinh.

Soon after, the #PlayersRights hashtag started trending on Twitter as the esports community received their first taste of good ol’ union busting that is so commonplace in other workplaces. The technique of singling out one worker in order to spook the rest has been used in industrial disputes for a very long time. The bosses’ aim is to break apart a solid body of unionised people in order to stop the momentum of demanding rights in the workplace. And esports tournaments ARE a workplace! Anyone thinking that playing video games and earning money is already a privileged position does not grasp the material history of leisure turning into labour. The vast majority of people’s hobbies—cooking, arts or physical sports—have already been turned into commodity industries, and as the biggest strand of entertainment in the world, gaming is no exception.

Industrial disagreements such as The Teams vs PEA could be avoided (or resolved better) if the individuals were part of an equivalent of the Professional Footballers’ Association—an organisation boasting 100% membership. With such bargaining power, it offers players numerous protections, including sickness arrangements, insurance in case of injury, post-retirement obligations, and representation in disciplinary proceedings (in which the PFA plays a central part).

Less than a year ago, the former assistant general counsel at the National Basketball Players Association Hal Biagas was appointed to lead a North American ‘League of Legends’ players’ association. Crucially, this was created by Riot, the developer of the game. Paul Kelly, the former executive director of the National Hockey League Players’ Association voiced some concerns about the setup:

Obviously there is certainly the potential for conflict of interest, and the potential for the ownership side of the sport to assert control over the players through [the association] if they’re the primary or only funding source.

Such a situation is far from ideal, and there is a long way to go.

The Dream

In contrast to many other labour sectors, esports competitors have a significant and resounding voice. Most of their activity is based online, and so they often amass thousands of followers on Twitter and Twitch, which means that their opinions are at least heard. Their brand becomes a currency.

Still, most of these people are fearful about appearing as troublemakers and will not make waves in the industry. If even the most well-known competitors are anxious about being mistreated by the boardroom executives who draft their contracts, what chance do the lower-tier players have?

If the leagues themselves will not cooperate in creating a sustainable, respectful workplace environment, one must start reimagining the structures for team ownership altogether. There is plenty of scope for co-operative models. For example, teams could pay salaries and other expenses via crowdfunding, resulting in players only needing to respond to their audience, instead of some invisible investors.

More fundamentally, the biggest difference between esports and any other non-digital sport is that creators of the game ultimately own the asset— if they go bust, so do the players. Analog sports do not have that problem— football or rugby are unlikely to disappear due to some company going bankrupt.

So how can the players own their means of production? These questions are being asked with increased intensity now that it seems likely that esports will be included in the next Olympic games. How would the Olympic Committee deal with the fact that the code used for one of their competitive sports is owned by a private company? The only way to make this work would be to communalise the code of the game, by making it open source and relinquishing any profits from it. Development companies would be desperate to persuade the Olympic Committee that their game should be hailed as the first authorised electronic sport. The name recognition gained would be enormous—studios would hardly even need to advertise their next title. Of course, broadcasting rights and advert minutes are currently sold to individual corporations, but playing a sport that is fundamentally linked with an existing business, does that bend the aspirations of an Olympic Endeavour slightly too much?

On the other hand, esports emerging on such a grand platform as the Olympic Games may shine a light on many shifty industrial practices that are currently common in the Wild West that is competitive gaming. Performing at the Olympics will certainly further legitimise esports activities, so it is only fair that the years of training are recognised with improved work conditions. Competitive players sacrifice years in order to perfect their techniques—if they are set to start bringing national glory to their respective countries, they must use that leverage in order to gain the material security enjoyed by their ‘analogue’ counterparts.

Conclusion

Esports has come a long way from its humble beginnings in the arcades— it is now a billion dollar industry and is likely to grow further. Although a few lucky names in competitive gaming have been able to establish their financial security and retirement funds, no real structure exists for other workers to defend their rights.

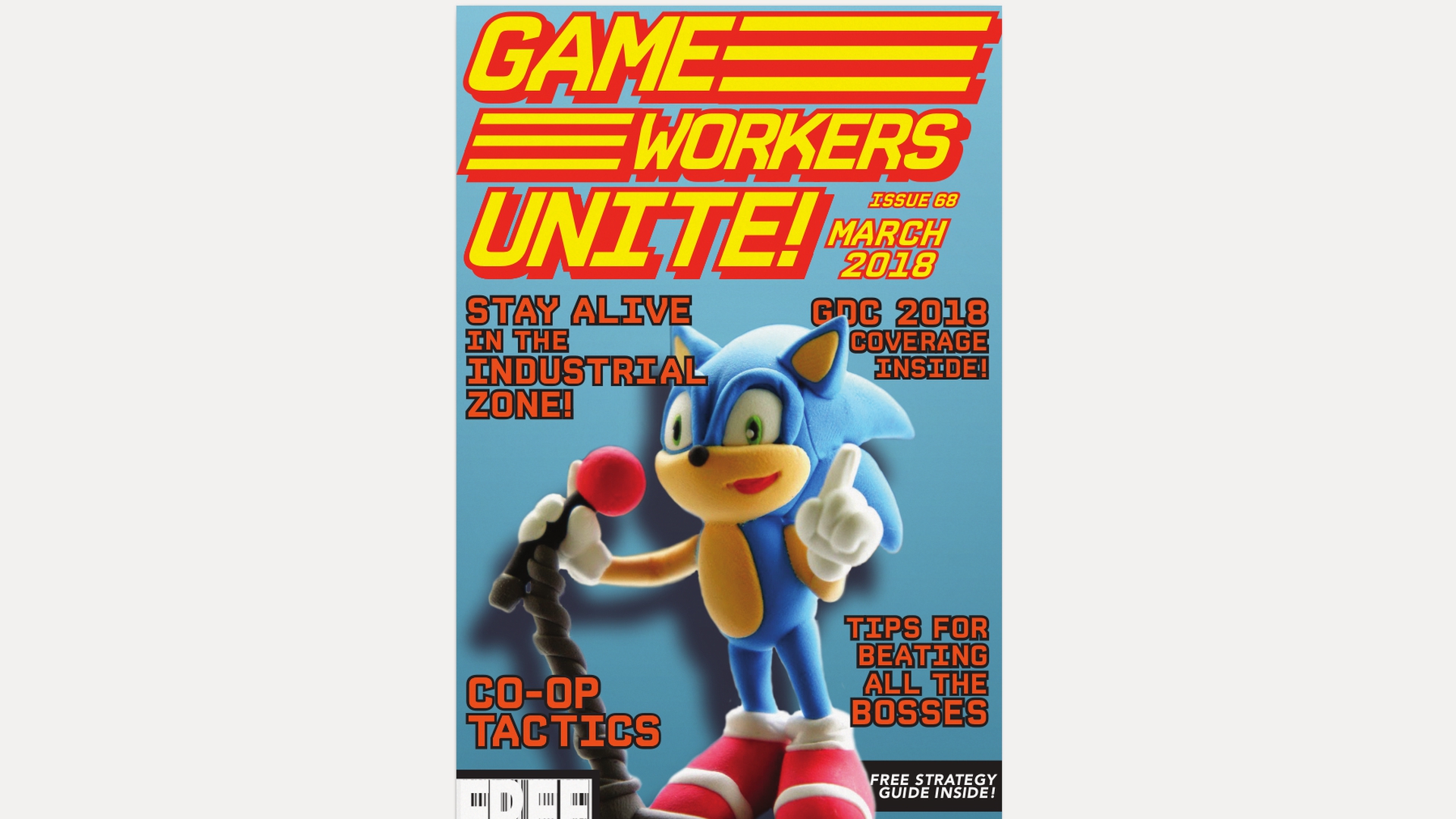

For decades now, individuals working on the development side of the games industry have convinced themselves that they are lucky to be getting paid for doing what they love doing. This attitude is beginning to shift, however, as these developers catch on to the fact that their labour is creating vast profits for others. Hence the demands for change expressed in this year’s Game Developers Conference. Esports players must face up to the same reality—although being paid to play games sometimes feels like a privilege, it is nonetheless accumulating vast capital for others, and only by unifying the workforce will the players have any input as to how that capital is spent. While their basic instinct is to compete, pro gamers will find that only by working cooperatively and establishing collective bargaining powers can they bring down the final boss.

We have little time to waste. It’s likely that leagues will soon start employing professional union busters to stall the organisational forces. Books, videos, seminars, and consultants aid employers in their attempts to convince the employees that staying ‘union-free’ is in their best interest. A long lineage of industrial organising informs us that we can only expect more of such techniques.

The time is right to build on the momentum of GDC and create a body of lawyers, full-time advisors, organisers, and researchers that would equate to something along the lines of an Independent Esports Workers Union. The purpose of such a collective would be to become a first resource for advice and, if necessary, defence against the industry. One may think that the competitive gaming industry is too precarious and volatile, but examples show that if even Deliveroo and Uber drivers can get organised and achieve results, there’s nothing stopping professional gamers doing the same.

Let’s make it happen in 2018.

Hasta la victoria siempre!

-

In the confusing world of esports, PEA is only a single league rather than an equivalent of PFA. ↩

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

author

Marijam Didžgalvytė (@marijamdid)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Players as Workers: Who Will Profit?

by

Patrick Prax

/

March 30, 2018