Editors' notes on class composition and technology

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

March 30, 2018

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

On the relationship between class struggle and technological development and the contradictions/limitations of automation

theory

Editors' notes on class composition and technology

by

Notes from Below

/

March 30, 2018

in

Technology and The Worker

(#2)

On the relationship between class struggle and technological development and the contradictions/limitations of automation

At its simplest, labour is how we interact with our environment. The point of this interaction is to meet our needs in order to survive. For most of human history, our interactions directly provided for our own subsistence. The first tools simply increased our ability to produce for ourselves. Those first primitive tools had immediate uses: spears killed things, clothes kept you warm, and so on. But as human society developed, so did our tools. Now, many of our tools have only an indirect relationship to our immediate subsistence needs. Lines of software code only lead to having food and shelter through a process of mediation via the complex division of labour of modern capitalist societies.

It is easy to think of the development of technology as a linear process: as inventions followed by more inventions. However, this is rarely how technology develops in practice. There are often multiple options, dead-ends, and lost possibilities. Technologies are not neutral. They are designed, made, and used by people within existing social relations. For example, Noble1 showed how automation in the factories could have been achieved with either numerical control or record-playback. Numerical control came to dominate as it better served the interests of capital, rather than because it was technically superior.

Under capitalism, technology is not just technology. Technology is used by – and on – workers. If we start with workers struggle, we begin with a different understanding of technology. For example, in The Poverty of Philosophy2, Marx writes that:

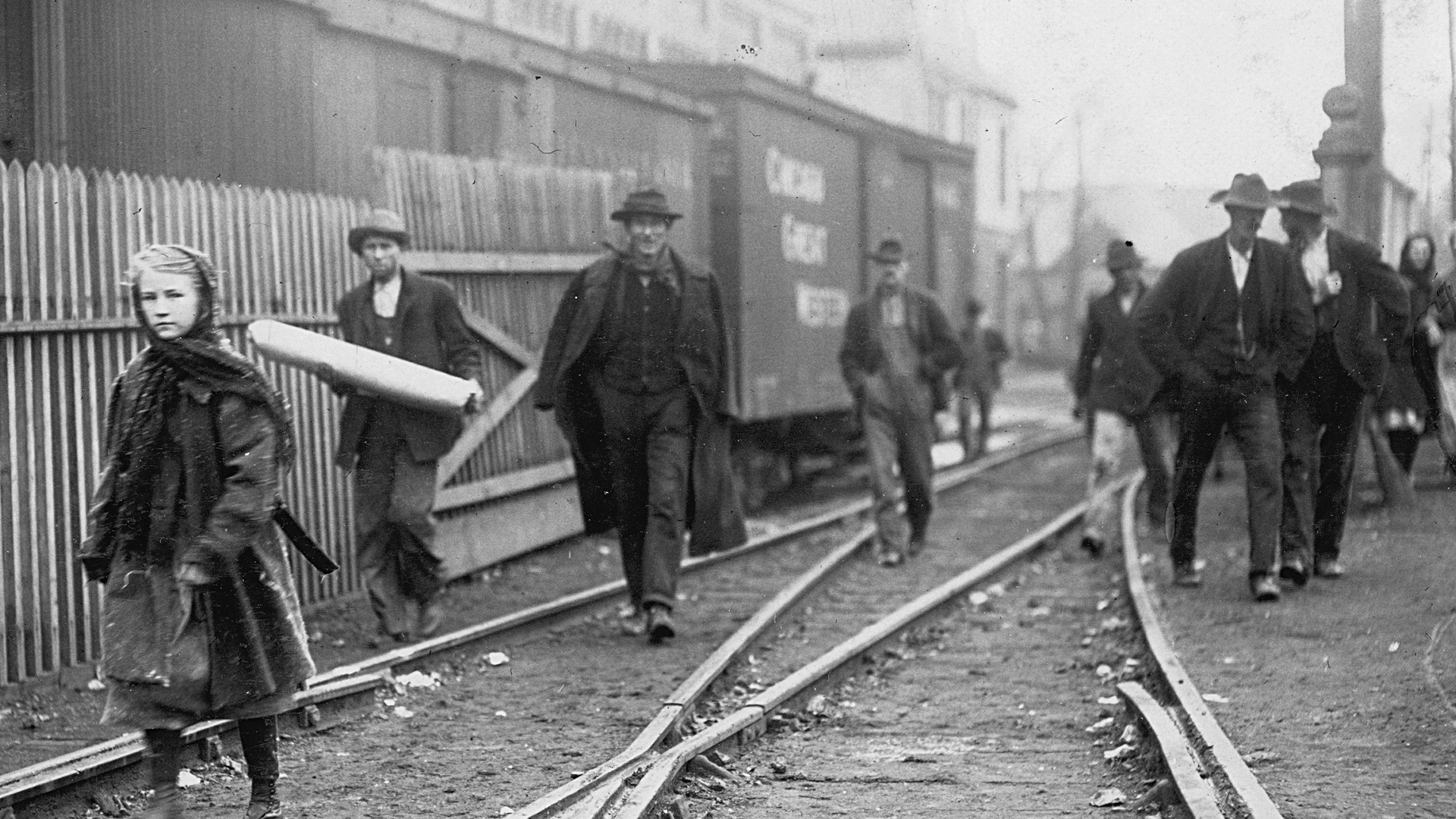

In England, strikes have regularly given rise to the invention and application of new machines. Machines were, it may be said, the weapon employed by the capitalist to quell the revolt of specialized labour. The self-acting mule, the greatest invention of modern industry, put out of action the spinners who were in revolt. If combinations and strikes had no other effect than that of making the efforts of mechanical genius react against them, they would still exercise an immense influence on the development of industry. […] Of all the instruments of production, the greatest productive power is the revolutionary class itself.

Here we can see how workers’ struggle forces capital to respond by using technology to break up the labour process, and thereby disrupt working class self-organisation. In another passage on technology, Marx argued that ‘it would be possible to write a whole history of the inventions made since 1830 for the sole purpose of providing capital with weapons against working-class revolt.’3 Exploitation has never been a straightforward process for capital. It involves increasingly complex ways to supervise, control, coerce, and motivate workers. For capitalists, one of technology’s main uses is technological repression.

When we analyse class composition, we begin by thinking about the technical composition of work. An integral part of this is how technologies are used at work. As workers, we do not relate to the technology used in our labour processes as an exciting and liberating potential. Instead, we most often see it as a way of intensifying work. You can see this in the way that Supermarket workers identify their scanners as ways of measuring and aggressively setting targets, call centre workers under intense supervision, or in the relation to technology in the poetry of Foxconn worker Ziu Lizhi:

我咽下一枚铁做的月亮

I swallowed a moon made of iron

他们把它叫做螺丝

They refer to it as a nail

我咽下这工业的废水,失业的订单

I swallowed this industrial sewage, these unemployment documents

那些低于机台的青春早早夭亡

Youth stooped at machines die before their time

我咽下奔波,咽下流离失所

I swallowed the hustle and the destitution

咽下人行天桥,咽下长满水锈的生活

Swallowed pedestrian bridges, life covered in rust

我再咽不下了

I can’t swallow any more

The use of technology to de/re-compose work is different across the world, but becoming increasingly connected. The final line of the poem points towards refusal, a key part of understanding class struggle.

On Automation

This refusal has been and continues to be present with technology. It cuts across what Panzieri called the ‘objectivist ideologies’ of technological progress4. These are particularly present with discussions around automation. Historical process of automation (whether partial or not) in the factory system was a response to working-class refusal and struggle.

Automation appears as an attempt to increase capital’s control of the workplace. For Tronti , the ‘political history of capital’ can be read as a ‘history of the successive attempts of the capitalist class to emancipate itself from the working class.’5 This can be found with the increasing use of machinery in comparison to workers in production – what Marx called “the organic composition of capital.” It can also be seen with the rise of automated vehicles and the spectre of robots coming to take all of our jobs.

The problem, for capital, is that capital ‘itself is the moving contradiction’, in ‘that it presses to reduce labour to a minimum, while it posits labour time, on the other hand, as sole measure and source of wealth’6. This is not to say that automation won’t happen, but rather that the way automation is introduced is differentiated and contradictory. It destroys jobs in some areas, while creating others elsewhere.

There are two main problems with how automation is discussed today. The first is a sense that automation is a new thing. Historically, the machine is an attempt to automate part of the labour process, increasing the amount produced by a worker. It has a significantly longer history than self-driving cars or automated warehouse pickers. Marx explains how in the factory:

The special skill of each individual machine-operator, who has now been deprived of all significance, vanishes as an infinitesimal quantity in the face of the science, the gigantic natural forces, and the mass of the social labour embodied in the system of machinery, which, together with these three forces, constitutes the power of the ‘master’.7

This lead us to the second problem: there is often a binary understanding of automation, either something will be automated or not. This leads to a focus on the machine – how effective is the new self-driving vehicle – rather than looking at how automation is actually affecting work and workers. Rather than an either-or, automation is used much more as an augmentation of the labour process.

For example, call centre workers have had much of the labour process automated. There is no need to find the telephone number, dial the number, pick up the receiver, find the customer file, think of what to say, and so on. Instead, the call centre worker can focus on the scripted selling of some product. It is true that some jobs are likely to be drastically minimised with automation. The classic example is driving. However, the push for automated vehicles is also creating huge numbers of new jobs. This includes the relatively well paid software development jobs, along with the vast amounts of low-paid click-work used to train algorithms.

When considering digital technologies, automation is often seen as inevitable. In part, this is because digital technologies are about computation. Computation involves programmed instructions for a computer to automatically carry out. This sophistication of modern software means there has been a huge growth in complexity. It has become near-incomprehensible to most workers.

The design, writing, and maintenance of software requires human labour, running on hardware that involves labour in various ways. Software has particular uses, running on different kinds of hardware in various context. The speed of innovation means that software requires regular updating and risks rapid obsolescence if it is not maintained. Therefore, it is only through the use of software, both maintaining it and using it, that ‘living labour’ – to borrow again from Marx’s – ‘seize[s] upon these things, awaken them from the dead, change them from merely possible into real and effective use-values.’8

Although the automation has become a popular topic recently, it is not necessarily always the solution for capital. Machines are not always cheaper than labour. A good example of this is the number of automated car washes across the UK that lie idle. Instead, migrant workers do the same work in car parks for a fraction of the cost. Instead, we should see automation as contested. There is no doubt that software will continue to transform work, but capital still cannot emancipate itself from the working class. Instead, work becomes divided and shifted across the world in new ways. And if capital were to succeed, the results would be bleak for all of us.

So why this special issue?

The issues discussed above highlights why a class composition analysis has to integrate a critical understanding of technology. This meant we knew we wanted to address these in a special issue. Given we seek to start from a working-class perspective in Notes from Below, it made sense to us to ask Wendy Liu and Marijam Didžgalvytė to curate an issue on tech. Wendy’s writings in issue 1 showed a rare insight into tech work, while Marijam has been at the forefront of critical analysis of technology in the UK. These guest editors have compiled a fantastic issue on class composition and technology, drawing on the experience of workers.

At Notes from Below, we are excited to be forging links with the Tech Workers Coalition (TWC) and Game Workers Unite. This is particularly due to TWC discussing and using workers’ inquiry in their organising efforts, something we’re keen to encourage across different sectors. This moment of potential political recomposition is break from the uncritical acceptance or rejection of technology. Instead, and understanding of technology is developing that can be informed by the struggles of those who design, build, maintain, and use technology – or indeed have it used against them.

The framework we laid out in issue 1 provides a guide for understanding technology from the perspective of the working class. This means understanding how technology impacts the technical, social, and political composition at various points. We need to understand who designs and makes these technologies for capital (and under what pressures), what new forms of exploitation emerge, and how technology is transforming work and life more generally. This is understanding is important. Not to understand the ‘technological rationality’ of capital ‘in order to acknowledge and exalt it’ – as perhaps too many are at risk of doing – but ‘rather in order to subject it to a new use: to the socialist use of machines’9 . And we see this issue as one step towards that goal, from the factory floor to the most complex AI software.

-

Noble, Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation ↩

-

Marx, The Poverty of Philosophy ↩

-

Marx, Capital Volume 1 ↩

-

Panzieri, The Capitalist Use of Machinery ↩

-

Tronti, Strategy of Refusal ↩

-

Marx, Grundrisse ↩

-

Marx, Capital Volume 1 ↩

-

Marx, Capital Volume 1 ↩

-

Panzieri, The Capitalist Use of Machinery ↩

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Workers' Inquiry: A Genealogy

by

Salar Mohandesi,

Asad Haider

/

Jan. 29, 2018