Editorial: Left in Our Care

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

November 17, 2025

Featured in Hammering the Sky: Collective Action in Care (#25)

Our editorial for Issue #25: “Hammering the Sky”

inquiry

Editorial: Left in Our Care

by

Notes from Below

/

Nov. 17, 2025

in

Hammering the Sky: Collective Action in Care

(#25)

Our editorial for Issue #25: “Hammering the Sky”

the turnaround of managers

that supervise the region

is not far from the turnaround

of low paid unit carers.

They come and go

& switch their manic faces

like the Doctor;

casting at us falsities and shit.

We wonder how

in faith we might

with tenderness

support them.

The things your type prioritise

are shit, more than I know;

but the things we can achieve

together are amazing!

Like curtaining the hallways

or hammering the sky

(Verity Spott, ‘Click Away Close Door Say’)

In this issue of Notes from Below, we focus on the social care sector in Britain. While putting together this issue, the far-right led 150,000 people through the streets of London, with just a couple of thousand counter-protestors in opposition. They marched under the windows of St Thomas’ Hospital, staffed mostly by migrant workers of colour, and broke through the barriers put up to protect the hospital grounds. Workers successfully fended them off, but many non-British workers spent the night in the hospital because they did not feel safe leaving.

This is yet another example of the far-right’s attacks on care workers, which the Labour government has once again capitulated to. Against the backdrop of a recruitment and retention crisis in social care, the Conservative government expanded the Health and Social Care visa in 2022 to include care workers. Since then, over 200,000 people have migrated to Britain to be care workers. Five such workers detail their experiences in Caring on a Visa and in In The Country and the City. The Labour government recently announced its intention to end the Health and Social Care visa scheme. In response, Linden Kemkaran, despite being the leader of the far-right Reform-controlled Kent County Council, wrote to the Home Secretary appealing for the visa to continue.1 Workers on these visas are pulled between these contradictions: a right-wing government introduced the scheme, the Labour Party pulled it, and the representative of an anti-migrant party has called for it to continue.

The Health and Social Care visa was never perfect, and, like many other schemes, contained an important caveat: the visa itself was held by the employer. In practice, this meant that the visa was offered by the employer to any interested workers abroad. If accepted, workers then move to Britain on the condition of the employer’s sponsorship. This means they can only stay in Britain on that same sponsorship, unless they are able to find another employer to switch to - something that can prove difficult to do. This arrangement of the visa scheme is ripe for exploitation. It can see intermediaries or employers charging workers thousands of pounds in fees to move to Britain, some as high as £30,000. While these fees are illegal, many workers applying for the scheme are told it is a condition, and do not have any meaningful recourse to challenge it from abroad. To pay these fees, many workers sell their houses, cars, and land in their home countries. They might even borrow money from friends, family, or take out loans. This can mean that there is nothing left for them if they return home, or that debt is waiting for them.

A rush of new visas was issued once the scheme opened. Many smaller employers in the sector saw this as an opportunity to make money with relatively little oversight from the British government. It also created an incentive to over-recruit. It mattered less to the employer if they could not provide hours to those recruited on the scheme, if they had charged them all fees for the visa. This creates another contradictory situation for care workers. They find themselves recruited to fill the growing vacancies in the sector, but end up working for a care company with too many workers and too few hours. This also does not mean there are no working hours available in other parts of the country or at other companies.

Those who do have work often report working twelve-hour days but being paid for four. It is common for employers to claim that they do not offer sick or holiday pay. Some employers are not paying tax. It may well show on a worker’s payslip, but there are no records with HMRC. In addition to charging fees and stealing wages, many employers offer accommodation to workers moving to Britain, only for workers to find on arrival that rent is significantly above market rates and automatically deducted from their pay. There is a common dynamic that these companies are owned or run by migrants from the same country that migrant workers are arriving from. They may have roles that are seen as “trustworthy”, like doctors or pastors, using their community connections to offer visas in their home country. From these experiences of workers, we can see that the visa scheme has not provided a straightforward route for migrants to begin working in care in Britain. Instead, a secondary market of Health and Social Care visas has been created, with the standards of care driven down further and further. For instance, a BBC undercover investigation found that a practicing NHS doctor had established a care agency called “Efficiency for Care”. In 2022, they employed 16 workers. Only a year later, they claimed to be employing 152 workers. Between March 2022 and May 2023, they had issued 1,234 Certificates of Sponsorship to care workers for their visas. The sponsorship licence was revoked after it was discovered that many of these jobs did not exist.2

The provision of care in Britain increasingly relies on these global care chains. However, when workers are recruited to care work in another country, this can also leave people uncared for back home. There have been many stories of migrant care workers describing the difficulty of leaving their caring responsibilities behind at home (often to older relatives) in order to travel to provide care work in another country. These care chains build upon the historical relationships of imperialism, while creating new forms of international extraction, mediated by increasingly hard borders.

The Politics of Care Work

Despite the widespread chaos that the visa scheme has caused, it also draws stark attention to the current problems with how the care sector is organised. Migration is only one dynamic within a broader sector that is under immense strain. Care work is a site of important struggle over what it means to work in Britain today, including who gets to work, under what conditions, and what kind of services their work provides. The sector is politically and strategically important for these reasons, as well as being central to how the working class is produced and reproduced in Britain today.

Every worker needs care at some point in their lives, and an increasing proportion of those needing care are purchasing it in a commodified form from care agencies. Social reproduction can rely on activities that are ‘directly market-mediated’, like care work, and ‘indirectly market-mediated’, where those same activities might be happening but unpaid.3 This builds upon and develops the historical gendered divisions of labour, including what is recognised as work, what is unpaid, demanded for free, and so on. At the same time, as many of those who historically provided unpaid care are drawn into paid employment, a larger share of the care work they shoulder is now carried out by formalised care workers.

Adult social care work (whether paid or unpaid) most often concerns those historically constructed as unfit for work. This means people deemed below the physical and mental threshold for exploitation under capitalism. In this sense, social care work reproduces the lives of surplus populations for their own sake, rather than serving the capitalist imperative to reproduce only what directly sustains productive labour. The fact that the state remains partially bound to reproducing capital’s leftovers - whether those depleted by decades of exploitation or excluded from the outset - shows that life beyond capital still holds some social priority. Yet the growing push to privatise social care, to detach it from public obligation and depress working conditions, indicates that this priority is being eroded. From this perspective, austerity can be seen as an expression of the sharpening class struggle that surrounds the value of ‘unproductive’ lives.

All of us have some experience of care, whether giving, receiving, or both. However, while care work (in the directly market-mediated sense) is increasingly important for reproducing the working class, many of us do not have a direct experience of the conditions under which that work happens.

There are different technical compositions of care work that require attention. In some kinds of care work, technologies usually used by managers to exploit workers can be repurposed or reframed as facilitating carers to do their work well. These might be technologies used to render care recipients more ‘manageable’ under the presumption it is for their own good. It is therefore essential to understand the extent to which care and forms of ‘management’ intersect. Care work often involves supporting the self-regulation and management of care recipients, and this crossover between ‘managing’ and ‘caring’ can become complicated. Surveillance in some care workplaces can be seen as a means to regulate the workplace, enabling workers to do their job more effectively, supporting care recipients better, and generating evidence that can protect care workers from misconduct claims made against them. In most public sector contexts, these kinds of technological surveillance systems are taken for granted (e.g. hospitals, care homes, and so on). However, these changes significantly shape the technical composition of the work and also raise important questions about how we might organise care differently.

Understanding social care is key to understanding working class existence more widely, both as care providers and care recipients. There are no workers without care. Care workers are also increasingly taking on care provision that would otherwise limit the work other workers can do. Not only does health and social care have the highest percentage of workers in the economy (13.5%), care work is the most common paid form of work for women in Britain. It is central to understanding the contemporary gendered division of labour and the army of women who care. This division of labour is neither natural nor biologically determined. If we want to break the idea that this is women’s work, we need to socialise the work of care. This begins with organising as care workers.

This issue has additional significance in understanding the class composition of Britain because we attempt not only to analyse the class composition of a specific sector, but in doing so, we reveal something about the social composition of all workers. Who does the care work so we can go out and work? Who cares for us when we can no longer work? We are also facing the reality that demographic changes in Britain mean that care work is only going to increase. There is an ageing population, but there is also an increasing number of young people who need care. The current reality is that more people need care, and our society is failing to provide it. This opens up a significant organising opportunity - but also one that is an increasing necessity.

Organising in another unorganisable sector

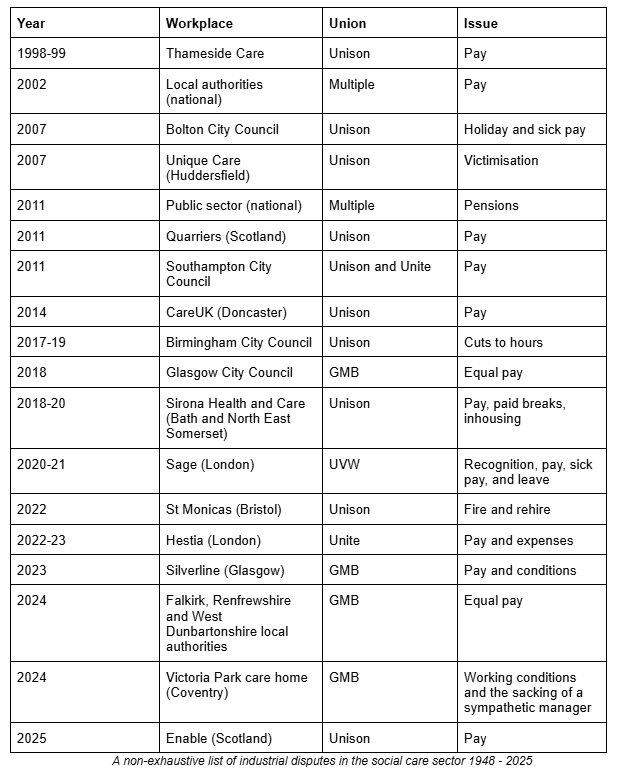

Social care shares many features with so-called “unorganisable” sectors: insecure employment, high turnover, small and dispersed workplaces, and a disproportionate concentration of migrants. Readers of Notes from Below will be familiar with other sectors in which these claims have been made before. This has not stopped workers from finding new ways to organise themselves. However, in addition to these general features, another barrier to organising more specific to the sector arises. There is a genuine anxiety many workers feel about causing harm to the people they care for. Beyond just anxiety, many workers actively identify with the social value of their work. This combination has traditionally led employers, trade union organisers, and workers themselves, to conclude there is no hope for a serious workers’ movement to take root in the sector. This is not without some historical evidence. From the modern origins of the sector in the 1940s to the present day, social care has been notably lacking in workplace militancy. However, as this issue illustrates, this historical pattern no longer holds true.

From the mid-2010s through to the present day, and especially since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, the sector has seen historically unprecedented levels of industrial action. It is worth taking a moment to fully absorb that fact. This crucial sector, key to the organised reproduction of our very lives, has become a new battleground in the struggle between classes. Marketisation, followed by savage austerity, has driven a new generation of carers to reassess their coworkers’ historical hesitancy to strike. Two participants in this wave of strikes share their experiences in Enable Scotland: Leading the Way and How to Run a Strike in Private Care.

The scope of this issue is heavily influenced by this new wave of struggle. As editors, we decided to focus mainly on adult social care, particularly on workers undertaking personal care, for a range of reasons, some personal and some political. First, we thought it was essential to highlight the significance and unprecedented nature of this new wave of militancy, and therefore to prioritise contributions relevant to this part of the sector. Second, as editors, we have more commonly worked either with or as adult care workers, undertaking personal care ourselves, and therefore have more familiarity and contacts in this area. And third, in the wake of the new wave of ‘Social Reproduction Theory’, there has been a tendency to theorise about “life-making activities” in extremely expansive (and often quite abstract) terms.4 We wanted to do some gentle stick-bending, drawing attention back to these concrete experiences of workers’ self-organisation.

As a result, with the exception of foster care, we have omitted children’s social care. We also have not included the experience of social workers, who we should note are also waging their own minor strike wave.5 We have omitted writing on the experience of unwaged care, except where it relates to the experience of waged care workers. We view these areas as equally important and would welcome contributions for future publication. This time, however, as always, there is only so much one issue can hold.

Social Care and Party Politics

The themes discussed in this issue are particularly pressing. As the example of the Health and Social Care visa shows, there is currently no political party with a serious proposal to address the care crisis in Britain. There are some glimpses of what a proposal could look like, for example, the National Care Service. However, this is really just a slogan that recognises the problem. There is no concrete plan to actually address it. Similarly, the plan for sectoral bargaining in adult social care will not, on its own, solve these problems. It is, of course, down to workers getting organised and using their own caring labour-power as a weapon against the employers.

Workers in the sector are also likely to face significant new challenges as the parliamentary power lurches towards the far-right - both from the current Labour Party, the ascendant Reform, and whatever kind of government will come next. Many care jobs are funded by the state, whether directly, subcontracted, or indirectly. This means that local councils, with their elected representatives, make decisions that affect the terms and conditions of these workers. While a Reform-led council may have petitioned the Labour government to extend the visa scheme, this position will likely change.

There is a long history of public sector unions being closely aligned with local councils. Often through shared membership of political parties, or through a range of other personal and organisational links. For some unions, this deeply compromising position is going to be thrown into stark relief as the dominant political parties have either collapsed or are on the verge of collapsing. For many unions, this means either finding a new relationship with local councils, either directly confronting and fighting them - or in the case of newly led councils with progressive agendas, finding ways to ensure that workers can organise within this new set-up.

More broadly, there are potential similarities here with other emerging struggles of public sector workers. As higher education workers increasingly find that their own struggles cannot be resolved at the local level, new strategies to address sector-wide funding are being experimented with. For example, the national dispute with the Secretary of State for Education over the funding model for higher education.6 In social care, there is often not enough money at the local government level to improve provision or working conditions. This means that more money needs to be allocated by the central government. And this will not happen without a fight.

Privatisation and the Future of Class Struggle in Social Care

The current struggles in social care follow historical changes in the sector. During the first phase of privatisation of social care work, roughly 1990 to 2011, the sector became composed of thousands of small residential and domiciliary care providers, as it remains today. They often employ a relatively small number of workers and provide services to a single local authority. In the midst of this highly fragmented market, private equity firms plowed in, buying up companies and building new residential homes. A small number of these firms achieved a very significant, heavily debt-driven, market consolidation. The strategy was based on access to cheap credit and guaranteed demand via local authority contacts, a strategy which fell apart with the austerity of the 2010s. In 2011, the collapse of Britain’s largest care home provider, Southern Cross Healthcare, signalled a turning point for capital in the sector.

No longer able to rely on local authority contracts, corporate care companies increasingly targeted clients with enough money or assets to buy their own care, so-called ‘self-funders.’ Such a market in the UK exists primarily because of the Right to Buy scheme in the 1980s and subsequent asset price inflation, which combined to create a pool of people with property they could sell to fund their own care. This pool has been large enough to maintain the private care industry, but it is nowhere near large enough to meet actual social need. The resulting ‘care deserts’ and take over by ‘real estate investment trusts’ is detailed in The Political Economy of Social Care.

Since the early stages of privatisation, social care has been undergoing a slow and uneven shift from a public service to a fully commodified, for-profit industry. But this has never been a linear process as the present landscape shows, with multiple forms of provision coexisting in a tightly interconnected ecosystem. On one side, remnants of public provision survive. But chronic underfunding erodes both working conditions and, by extension, the quality of care. This leads ultimately to outsourcing and market-led provision. Alongside this, thousands of small contractors operate as parasitic intermediaries, siphoning off surpluses from public contracts. This is money that could otherwise be spent on care. Like other outsourcing arrangements, these firms generate profits through extreme employment deregulation, wage suppression, exploitative visa regimes, the downgrading of standards, and, in some cases, outright corruption.

At the other end of the spectrum lies fully private provision, which follows a more straightforward market-based logic while still profiting indirectly from the wreckage of the public sector. This segment has increasingly turned to financialisation, attracting large flows of capital to scale up provision. Yet its growth model is unstable: with households unable to meet the inflated cost-of-living, providers are often left dependent on debt-driven expansion and speculative investment rather than sustainable demand.

The crucial element for us in all this is the place of class struggle. In particular, the points of political alignment forming among workers moving through these different arrangements, and how their industrial activity might shape the direction of broader structural shifts in the sector. A significant case study here is the struggle of subcontracted workers in Bath and North East Somerset, who successfully pushed for care services to be brought back under direct council control. Following a two-year dispute, subcontractor Sirona Care and Health announced in early 2020 it would hand back the contract for three residential care homes and five extra care housing schemes, after the provision had become “financially unsustainable.”7

What this episode shows is that, unlike hospitality or other industries with relatively low profit margins, bankruptcy does not have to be an obstacle to action. In fact, since councils have a legal obligation to provide and maintain care services, workers bankrupting their employers through strike action may actually represent an indirect route to in-house provision. How such a worker-led strategy intersects with a national programme for repatriating care to the public sector, remains an open strategic question. But it certainly shows points of weakness in the current system.

Generalising such a model across the many parasitic operators that dominate domiciliary care, given the extreme constraints of this work, raises many important compositional questions. There is one thing that is certain: workplace struggle in this sector will continue to be a crucial testing ground for new forms of worker organising. Its power in the broader class struggle will lie in its ability to re-imagine the meaning of care itself, and in challenging the authoritarian regimes of management and government that so starkly betray it.

Summary of the Articles

In The Political Economy of Social Care, Lydia gives a critical overview of the social care sector in Britain. She lays out where and for whom care workers work, as well as laying out the systemic pressures workers face. Despite this, there are exciting organising opportunities and emerging worker-driven efforts.

In How to Run a Strike in Private Care, care assistant Tamara Beattie presents a standout example of the new wave of industrial organising in care. Tamara reconstructs how Silverline workers built up a strong enough foundation to beat off management attacks in 2023. In doing so, Tamara provides a step-by-step guide for building workers’ power in care.

In Enable Scotland: Leading the Way, workplace rep Tom Baylis talks us through the first national care strike in Scotland in over a decade. With more providers currently balloting, Tom makes the case for the necessity, and possibility, of coordinated action for political demands.

In Caring on a Visa, we pull together a collection of writings from workers who came to Britain on the Health and Care Worker visa since 2022. Four workers reflect on the reality of the work, compared to the dream they were sold, and the experience of being tied to your employer through a visa. Each writer also details the organising projects that have come from this.

In Moving Beyond the Terror: Care and Support Workers Organise, former members Alison Treacher and Steve North recount the rise and fall of a national, cross-union rank-and-file network in care. From brutal origins in the early days of the pandemic, Care and Support Workers Organise provided essential lessons for building independent workers’ self-organisation.

In We’re Not Waiting to Be Saved, local government workers Rana Aria and David Isaac share their experiences with Access to Work, a government support scheme for disabled workers. Bringing insights from ‘the other side’ of the care relation, Rana and David stress access and inclusion as priorities for political and industrial struggle.

In The Silent Profession: Foster Carers Who Hold It All Together, foster carer Sue Lloyd outlines the sober reality of contemporary foster care. Against the simultaneous exploitation and denial of their specialist skills, Sue argues that only democratic, grassroots trade unionism - under the control of foster carers themselves - can secure the conditions they, their children, and our society really need.

Finally, In The Country and the City: Unionising Rural Care Workers explores the often-overlooked struggles of rural and semi-rural care workers fighting to unionise in the midst of Britain’s care crisis. From Carlisle’s hospital wards to isolated community care routes and the precarious world of domiciliary labour, workers describe the realities of understaffing, low pay, and fractured supply chains of care.

-

Christian Fuller (2025) ‘Reform-led council calls for more social care visas’, BBC News. ↩

-

Tamasin Ford (2025) ‘Secret filming reveals brazen tactics of UK immigration scammers’, BBC News. ↩

-

Endnotes (2013) ‘The Logic of Gender: On the separation of spheres and the process of abjection’, Endnotes 3. ↩

-

For a review, see: ‘Social Reproduction’ by Marina Vishmidt and Zoe Sutherland ↩

-

We know of at least 8 strikes by social workers in the UK in the last couple of years; at Brighton and Hove City Council, South Gloucestershire Council, Barnet Council, Cumberland Council, the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust, two strikes at the Northern Health and Social Care Trust, and Lancashire County Council. ↩

-

Somerset Live, ‘Bath council takes back adult social care provision after repeated strikes’. ↩

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Contradictions in Care

by

Connor Cameron,

Lyra Unguent

/

April 24, 2024