Understanding our defeat

by

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1)

December 18, 2019

You can cut all the flowers, but you can’t stop spring from coming

inquiry

Understanding our defeat

by

Callum Cant

/

Dec. 18, 2019

You can cut all the flowers, but you can’t stop spring from coming

This article is an attempt to understand the 2019 General Election from the perspective of the Labour left.

We lost, and so we’ve missed one of the precious few escape trajectories that could have steered us away from late capitalist collapse. That single, vertigo-inducing fact is uppermost in all of our minds. The situation are now facing is worse than anyone expected.

I’ve argued before that there exists a gap between the advanced elements of the Labour party and the current level of working class organisation in Britain. At the same time as Labour under Corbyn has been advancing a meaningfully socialist programme on the terrain of parliamentary politics, the movement in the workplace and community has been in retreat. I said that this gap needed to close if Labour wanted to have a chance of implementing its programme in government. I would now retrospectively add that we also needed this gap to close if we wanted to have a chance at forming a government in the first place.

This gap between party and conditions of struggle on the ground is not a political gap: it’s not that we advocated policies on nationalisation, ownership, and public services which were too extreme for the British working class to support. Instead, it is an organisational gap: we proposed a programme that was premised on levels of working class organisation which do not yet exist. Alongside other factors, this contributed to our inability to win a majority within our (deeply flawed) democratic mechanisms - and would have made the implementation of that programme incredibly difficult had we done so.

The challenge ahead of us is first, to understand what happened during this general election, and second, to decide how we close that gap over the years ahead.

One thing seems clear - we cannot close the gap by falling behind, slowing down, moderating. Instead, we’ll close it by adopting a class struggle methodology, and bringing our ideas and forces to bear on the side of workers and tenants in the fights to come.

But despite the painful reality of defeat, no one seems scared of those fights. Talking to friends in the few days since the election, I’ve heard one theme over and over: a feeling of pride at having been part of a historic socialist movement, shoulder to shoulder with tens of thousands of comrades, old and new. A movement that looked the manifold crises of late capitalism in the face, and demanded that everything be for everyone. Most importantly, as well as that pride, there is a shared determination to build on our experiences together - and take the fight to the ruling class again at the next opportunity.

Class, Brexit, Turnout

The only intellectually honest thing to say at this point in the process of analysing our defeat is that we’re not exactly sure what happened last week. Rightly, there will be many, many post-mortems. But by combining an initial report from Datapraxis - the polling company closely associated with Labour who’s polling accurately predicted the outcome of the election - and the raw data from the Ashcroft poll, we can begin to get a handle on what the major features of the vote appear to be.

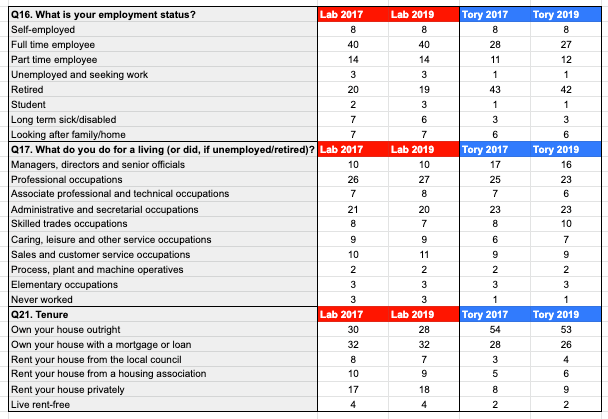

One of the most striking things to emerge from the Ashcroft poll is that on a national scale, there was no huge change in the class basis of either party during this election.

Labour remains the party of employees; the unemployed; the disabled; students; and private/social renters. The Tories remain the party of retirees; managers; and people who own their homes outright.

Labour lost three million votes compared to 2017, but it lost these votes broadly evenly from across the class fractions of its whole coalition. This doesn’t mean that there was not a tendency for home owners in the South East to be lost to the Liberal Democrats and social renters in the North East to be lost to the Brexit party - that may well turn out to be the case, as we come to understand the result better - but the overall national picture is one of continuity, not dramatic change. 1

Table 1. Lab/Con support 2017/2019 by employment status, job role and housing tenure (Source: Ashcroft)

But even if the voting base of the two main parties remained relatively constant relative to 2017 on a national scale, there were still strong variations in the way class influenced the vote on a local level. Resolution foundation analysis of deprivation shows a weakening in the historical relationship between voting intention and deprivation.

Figure 1. Deprivation and vote share (Source: Resolution Foundation)

Importantly, this is an analysis of electoral outcome in deprived areas, not a direct measure of the electoral behaviour of voters experiencing deprivation. So the change in vote share may well be more influenced by an increase in working class apathy or higher homeowner turnout than an increase in working class Conservative support. But regardless, the Conservative party won in constituencies like Blackpool South - and the impacts of these anomalies will take time to emerge.

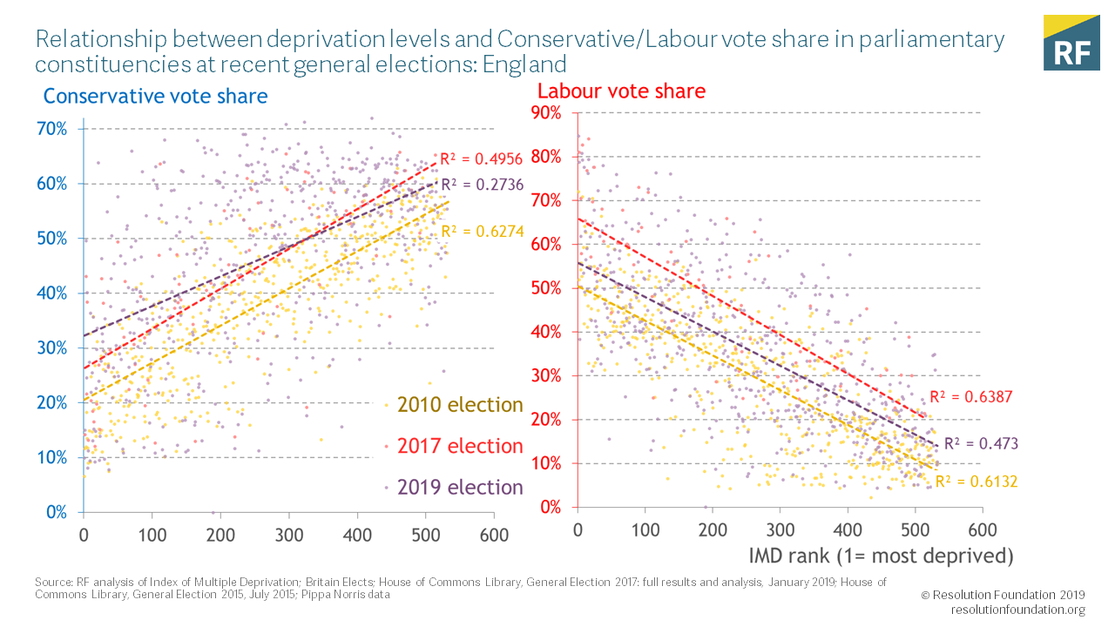

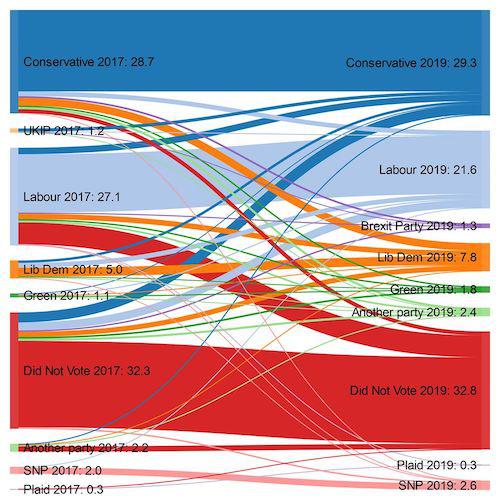

A second key trend in the election was the powerful impact of Brexit on voting behaviour. Analysis by Datapraxis has shown exactly how difficult the question of Brexit was for Labour. In short, they conclude that we lost voters both ways. 700,000-800,000 Labour Leave voters, many in so-called ‘red wall’ battleground seats, went to the Conservatives. Hundreds of thousands more either voted Brexit party or stayed at home and didn’t vote at all. On the other hand, 1.1 million Labour Remain voters (some also in the ‘red wall’) switched to the Liberal Democrats, the Greens or the SNP - alongside a surprising 200-250,000 Labour Leavers. These combined losses made the defense of leave seats very difficult, and simultaneously made offensive gains in remain seats almost impossible.

Our losses were particularly severe in some regions: over 13% of our 2017 voter total in the North East, 11% in Yorkshire and The Humber, over 8% in the Midlands, Wales, Scotland, and in the North-West and East of England. Importantly, these losses were not unidirectionally towards the Conservatives and BXP, but also towards the Liberal Democrats and abstention.

This is not to say that all these voting decisions were singularly motivated by Brexit - after all, Ashcroft polling shows that 55% of the electorate held the NHS as their top priority, compared to only 36% for Brexit. But it seems likely that a significant proportion of voters who swung away from Labour make their decision, at least in part. on the basis of Brexit.

The Brexit party single-handedly acted as a machine for turning Leave voters of various political backgrounds into tactical Conservative voters. Their agreement with the Tories to not run candidates in our offensive marginals in order to consolidate the Brexit vote must be seen in retrospect as one of the decisive moments of the election, where Johnson opened up the Conservative party to forces on their right in order to outflank Labour. Compare that consolidation of the leave vote with the antagonistic splitting of the remain vote. The ‘Unite to Remain’ alliance, led by ex-Tory Heidi Allan, relentlessly undermined Labour. Despite their public-facing position on two different sides of the Brexit culture war, an anti-socialist unity prevailed amongst politically diverse fractions of the ruling class.

Given this wider political context, it is my guess that Labour would have been highly unlikely to form a government regardless of what Brexit position we adopted at the start of the campaign. This is not to say that we ended up contesting the election on the best possible policy, or that we achieved the best possible outcome. In a counterfactual scenario, where an organised campaign had persuaded the membership of a socialist, internationalist Lexit policy at some point in 2016, Labour would probably have fared substantially better in this election. But as things stood, over 80% of members backed a second referendum policy earlier this year, making the Lexit position a brutally isolated one.

At an abstract level, if there is a split within the base of the party along class lines, the side of that split predominantly supported by the working class is likely to be the most progressive one. However, it is not at all clear, at this stage, if this leave/remain split amongst both members and voters was along class lines. As David Broder has argued, ‘it’s important to avoid stereotype here, especially when there is so much talk of “lost Labour heartlands” — or criticism that Labour is now a party for Putney but not for Wakefield. […] There are, indeed, millions of working-class people in London just as in ex-pit villages; a city like Liverpool, today among the strongest Labour bastions, has only fully been a real “heartland” since the 1980s.’

But one of the other fundamental factors in this election (which has received much less attention than the above) was the collapse in the turnout of the Labour vote. Nationally, overall turnout was down 1.5-2%, but in some seats the picture was more dramatic. In Stoke on Trent, it fell 19%, in Wolverhampton and Luton South it fell 12%. A comparison of the 2017 and 2019 general elections on the basis of the Ashcroft data (plus turnout data from other sources) indicates a highly significant swing from Labour to abstention. We will have to wait on further analysis to see who exactly made up this population - but their decision not to vote proved decisive.2

Figure 2. Swings in the vote share as a % of total electorate between the 2017 and 2019 general elections (Source: Ashcroft and Wikipedia, Credit: Phil Pope)

All of this remains a highly-provisional analysis. However, three hypotheses stand out: first, that Labour’s coalition is still led by the various fractions of the British working class (despite what may turn out to be specific local variations); second, that the question of Brexit split our coalition two ways and made victory difficult; third, that much of Labour’s 2017 vote did not turn out to vote for us this time around.

Air Supremacy

The Tory strategy in this election was straight from the playbook of the international far-right: combine a carefully workshopped core message with a relentless attempt to suppress the opposition vote through a billionaire-funded disinformation campaign. Then the Tory core vote - pensioners and the rich - was combined with a strategically crucial set of swing voters who were committed to the ‘Get Brexit Done’ slogan to produce thirteen million votes and a majority.

It is a campaign strategy that absolutely could not have succeeded to the degree it did without significant deviations from democratic norms and the emergence of a newly-reinforced alliance.

In 2017, Labour’s insurgent campaign took advantage of the fact that there was no coordinated strategy pursued by the media and the Tory party. This led to the popular argument that broadcast regulations were a key part of our rapid rise in the polls during the campaign, and that when Ofcom regulations kicked in we could reasonably expect fair treatment by the media. But this mistake on the part of the ruling class was not repeated.

This time round, broadcast regulations were blown out of the water. With the exception of a few notable moments where prominent presenters had their ego’s bruised by the refusal of Tory politicians to be interviewed, the Conservatives escaped all serious scrutiny - ducking debates and uncomfortable questions throughout the campiagn, while journalists soft-balled the few interviews they did get and reproduced attack lines verbatim. The different fractions of our dominant class put aside their differences, with nominal ‘liberals’ accepting the leadership of the far-right, in order to pursue an anti-socialist programme.

It’s a historical pattern which we’re not unfamiliar with, but it will take a while for us to come to terms with the fact that it has emerged here and now.

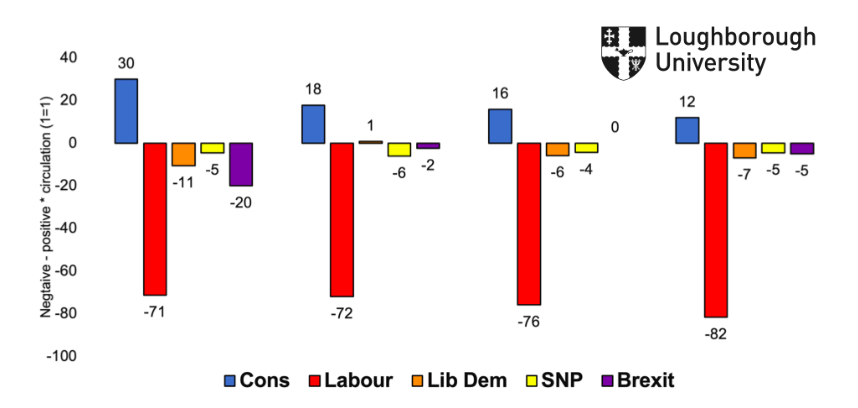

This access to an uncritical platform allowed the Tories to push their key disinformation lines over and over again. The actual details of this campaign deserve more attention in the coming weeks, but the preliminary outlines are clear. The research conducted by the Centre for Research in Communication and Culture at Loughborough makes for grim reading. The more notorious moments of the campaign: the Sun’s republication of a fascist ‘network map’ of the Labour left; Laura Kuensburg’s report of an assault on Matt Hancock’s aide (and subsequent apparent breach of electoral law), were in fact only minor episodes in a much more systematic assault.

Figure 3: Overall newspaper evaluations - weeks 1 - 4 weighted by circulation (Source: Centre for Research in Communication and Culture)

There were two central planks of this strategy: the use of disinformation, and the systematic representation of Labour as an illegitimate political force.

The disinformation campaign was consistent across print, broadcast, and social media and centred on the relentless repetition of two completely false figures: the £1.2 trillion total cost of the Labour manifesto and the £2,400 cost per family. Research by the Coalition for Reform in Political Advertising has shown that 88% of major Conservative adverts involved outright lies or misleading figures.

The most significant and under-reported component of the social media campaign was the large and concerted dark money voter suppression campaign conducted by ‘third party campaigners’.

Sham organisations like the ‘Campaign against Corbynism’ and ‘Capitalist Worker’ collectively spent hundreds of thousands of pounds systematically targeting Labour’s voting base with highly aggressive disinformation throughout the campaign. This material was designed to dampen Labour turnout - and it appears that it may have worked. This campaign even extended to putting up physical adverts outside polling stations in key marginals like Pennistone and Stockbridge on election day. Nearly every single registered administrator of these organisations are linked to the Tory party - and some are linked very closely indeed to Westminster Digital, the social media agency responsible for the Tories online campaign.

The delegitimisation of the Labour party was pursued particularly through the direct targeting of Corbyn. Datapraxis describe the effects of this targeting as ‘the most significant factor in Labour’s decline’. Swing voters were persuaded not to support Labour because this time round, the delegitimising attacks stuck in a way they did not in 2017. But this disapproval of Corbyn almost always operated, as campaigners on the doorstep saw over and over again, as a cypher for other kinds of perceived illegitimacy. Austerity realism on the terrain of economics took a battering in this election, with the Tories running on a platform offering significant increases in public spending. But this abandonment of the dominant political logic of the last decade coincided with the creation of a capitalist realism of a new magnitude, on the terrain of politics, which claims that there is no legitimate party of government that is not a representative of capital. It is against this political sense that we will have to fight over the coming years.

The question we have to ask ourselves now is why this strategy was so effective. In part, the increased cooperation of the media was a factor. But there is another factor at play: the isolation and disorganisation of the British working class. Gramsci made a distinction between ‘common sense’ and ‘good sense’. Common sense is the contradictory bundle of shared ideas in a society. Good sense, on the other hand, arises out of - but develops beyond - common sense, as a coherent and critical understanding of the world. In our current context, working class disorganisation has eroded the kind of thick ties through which ‘good sense’ circulates, and replaced them with a media environment in which the most destructive elements of ‘common sense’ are amplified.

The ongoing epidemic of social loneliness and isolation - stoked by the anti-collectivism of the last four decades - has made many people incredibly vulnerable to the confusions of common sense. You only have to think of the wildfire spread of rumours (some begun by fascists) that Corbyn condemned the police for shooting dead the London Bridge terrorists, or that the photo of the child lying on the floor of a hospital in Leeds was a set up, to see how huge sections of the electorate were convinced of rumours that influenced them to act in ways that were diametrically opposed to their material interests. When people’s everyday lives are lived in a state of constant alienation and isolation then you can dominante them by dominating their media system - and this is exactly what the Tory party managed to do.

Six weeks of near-constant mobilisation by mostly young and university-educated socialists, who left the major cities in huge numbers to fill key marginals, is not enough to reverse decades of collapse in working class organisation. Good sense cannot be recirculated on a national level in rapid fire doorstep conversations. The problem was not with the actual form of the movement. From the second the election was called, it went broadly as well as it could have done. But the problem was with the basis on which that movement operated and the lack of thick social ties to our voter base that we could call on - the problem was the top-heavy nature of Corbynism.

What was our movement?

Whereas the Tories dominated the air war, Labour dominated the ground game. The strength of the movement behind the party - in terms of raw resources - is unmatched in recent British political history. 170,000 people used Momentum’s My Campaign Map ( a data-driven recommendation engine which directed canvassers to marginals where the algorithm thought they could have the highest impact). That’s a remarkable 70% more than the number that used My Nearest Marginal in 2017.3 1800 Labour activists signed up as ‘Labour legends’ and contributed on average 2.6 weeks full time to the campaign, totalling 90 full years worth of campaigning in marginals. Polling day saw coach load after coach load of activists fan out from the major cities towards constituencies with a smaller activist base. The whole thing was structured by a huge network of WhatsApp chats which functioned both as organising channels and forums for political debate and a decentralised many-to-many communications infrastructure. Over six weeks, hundreds of thousands of people dropped everything to fight for hope. The warmth of 2017 was replaced by the grit of 2019.

In fact, the greatest success of this campaign is that we fought it well, as a movement. We fought it on deeply unfavourable terrain, on a flawed set of messages, and against the entire mobilised apparatus of the ruling class. But we fought it well. Seats identified as key marginals received significant activist support and did fare substantially better than the national average.

But this unparalleled activist mobilisation was not able to turn the balance of forces. This is important to understand: it is not that the movement was not actually big and powerful, that we all dreamt the unity and purpose of thousands of people across the country. It was that we were confronted by problems which were too deeply rooted to be resolved in six weeks

That is because, despite the relentless appeals and efforts of many movement participants, we have failed to build a ‘Corbynism from Below’.

2017-19 will come to be seen as a period where we were attempting to play a game of reverse Jenga: we had a socialist as the leader of the Labour party, an increasingly socialist programme for government, and hopes of electoral success - but no base in a mass movement, beyond the half million members of the party (many of whom were either unrooted in their local areas or completely inactive in the party.) The moevment’s highest acheivements were left balancing on a structurally-unsound base.

Many of us spent much of our time trying to back-fill that base, to add blocks to the tower, in order to put us on firmer ground. But this work never achieved neither widespread sucess, nor the support of the movement - some of which was convinced that it was time to ‘prepare for government’ rather than go back to basics. With notable exceptions (like the community organising unit), Labour and Momentum did not prioritise expending substantive resources on promoting base-building in the workplace and community. We have now paid the price for this strategic mistake.

Class Politics as Method

During the campaign, Labour picked up on the emerging problem in the ‘heartlands’. At one point, Datapraxis private polling showed that as little as 50% of Labour leavers were backing the party. Only a significant reorientation towards more aggressive class-led messaging managed to drag that number up to 61% by the end of the campaign - but it was too late to significantly change the result. Despite that, however, the messaging of the final few weeks should serve as an ongoing inspiration to the Labour left.

They're never going to keep us down.

— Jeremy Corbyn | Vote today 🌹 (@jeremycorbyn) December 10, 2019

Vote for hope on Thursday. pic.twitter.com/5a1ijJKwP1

This kind of emotional communication, that pinpointed an enemy and told people that it was time to fight back, is a clear contrast to what we were promoting earlier in the campaign. For the first few weeks, Labour presented a buffet of transformational policy to the country, rather than a programme of conflict with the ruling class over key bread and butter demands. We lost our sense of insurgency - and unlike 2017, the right were quick to pick up the mantle.

When ‘tax the rich’ is visibly a manifesto promise intended for technocratic implementation, rather than the demand of the majority of society backed up by serious class power, people are, quite rightly, skeptical. The billionaires have never paid tax when it was technocratically required before, and we didn’t seem to have the kind of movement that could force them to - so the inevitable response of a doorstep skeptic was disbelief. In that situation, a Labour canvasser was left in an odd situation, where they had to appeal to the effectiveness of HM Revenue and Customs rather than the power of our movement to implement higher rates of tax. Promising a totally transformative manifesto without the evidence of a totally transformative movement rings hollow.

André Gorz, in his seminal essay Reform and Revolution, argued something similar:

However eloquently it may be advocated by the opposition, a different policy will neither convince nor appear possible unless there has already been a virtual demonstration of the power of promulgating it, unless the relation of social forces has been modified by direct mass action which, organized and led by the working class parties, has created a crisis for the policies of the government in office. In other words, the power to initiate a policy of reforms is not conquered in Parliament, but by the previous demonstration of a capacity to mobilize the working classes against current policies; and this capacity of mobilization can itself only be durable and fruitful if the forces of opposition can not only effectively challenge current policies, but also resolve the ensuing crisis; not only attack these policies, but also define other policies that correspond to the new balance of forces, or rather—since a relation of forces is never a static thing—to the new dynamic of struggle that this new relation of forces makes possible.

Class politics is not a set of specific messages - it is instead, a methodology. If you advance socialist politics without the base required to implement it, people see through your claims. This is why class power is not an external problem to be confronted at the point of implementation - it’s at the core of the question of messaging, at the core of the question of electoral strategy. Labour’s failure to demonstrate that it could mobilise working class power is precisely why we failed to convince people of the manifesto.

Corbynism’s soft and friendly approach decisively hit its limit points. As Archie Woodrow argued just before election day: ‘we’ve pushed this leg of the project as far as it can go and it’s forced our opponents to take off the mask. It’s time to shift gears. Time to fight fire with fire. Time for Class War Corbynism.’

An Authoritarian Manifesto

The movement has to now adapt to the reality of being in opposition for a significant number of years. One of the first problems facing us is to work out what their immediate programme will be. Their manifesto was, by design, light on detail. It’s impossible to credit the idea that ambition of this new majority government will really be limited to Brexit and modest increases in public spending to below-2010 levels.

We have to get ready for a Brexit to take the form of a Turbo-Thatcherite assault, which sells itself as unleashing Britain’s potential whilst in fact systematically smashing our national regulative infrastructure. The NHS will, of course, be very much on the negotiating table when the US and UK governments meet to try and organise a fast track trade agreement. This might well be combined with short term investment, particularly in areas outside the South East - and that investment will create a link between a Conservative government and its new constituencies that we will have to work hard to break.

Most significantly for our movement, however, is the question of how this new government will maintain its power. Thatcherism always contained an authoritarian core, and so too does the programme of this new far right conservatism.

The Labour party can expect to face an attempt to ‘manage’ future democratic processes so as to insure against the possibility of a left resurgence through voter ID laws and boundary changes. This will be combined with their external support for an intensive anti-socialist campaign within Labour - during which the left of the party can expect to be defended by absolutely nobody in the national print or broadcast media.

Extra-parliamentary organisations can also expect a renewed wave of repression. The Tory manifesto promised to ‘combat extremism and do all we can to ensure that extremists never receive public money’. If recent research (sponsored by the UK Commission for Countering Extremism) into the newly-coined extremist doctrine of ‘revolutionary workerism’ and similar research by key Tory allies Policy Exchange into the climate movement is anything to go by, that definition of extremism will include most social movements.

On trade unions, the Tories are preparing to announce an all-out war with the union movement in their Queen’s speech, via a policy which would ‘require that a minimum service operates during transport strikes.’ Such policy has set them up for a direct confrontation with one of the most powerful industrial unions in the country, the RMT (alongside the TSSA and ASLEF, and potentially Unite if the legislation extends to bus and air travel). But this will not be the extent of their ambitions. Policy Exchange wrote the Modernising Industrial Relations research note that became the basis for the 2016 Trade Union Bill, and it included a series of measures including the elimination of the check-off of union dues via PAYE, the further restriction of picketing, and the legalisation of using agency workers as scabs that will be on the table if the rail unions lose.

Perhaps the most worrying part of the manifesto, as noted by Ben Smoke, is the section promising a systematic attack on traveller communities: ‘we will tackle unauthorised traveller camps. We will give the police new powers to arrest and seize the property and vehicles of trespassers who set up unauthorised encampments, in order to protect our communities. We will make intentional trespass a criminal offence, and we will also give councils greater powers within the planning system.’ The fear that this sounds proto-fascist will not be allayed by the news that, as of Friday the 13th, Tommy Robinson claimed on his Telegram broadcast channel to have joined the Conservative party.

We have lost the battle to escape the new global brand of far right authoritarianism before it takes hold. Now, alongside comrades in Brazil, Italy, Hungary, Turkey, India and beyond, we have to figure out how to destroy it from within.

Where we are, and where we want to go

If universal suffrage had offered no other advantage than that it allowed us to count our numbers every three years; that by the regularly established, unexpectedly rapid rise in the number of votes it increased in equal measure the workers’ certainty of victory and the dismay of their opponents, and so became our best means of propaganda; that it accurately informed us concerning our own strength and that of all hostile parties, and thereby provided us with a measure of proportion for our actions second to none, safeguarding us from untimely timidity as much as from untimely foolhardiness—if this had been the only advantage we gained from the suffrage, then it would still have been more than enough. 4

Engels was right to argue that elections offer us a chance to reflect on our strength. Despite the weakness of our movement in terms of organisation, we still rallied ten million people to a socialist manifesto. But if we want to start winning within the kind of timescale required by climate collapse - or indeed any other of the litany of ongoing collapses - then we need to build an organised and mobilised base in the most efficient way possible.

My guess is that the most important part of this process will be converting the hundreds of thousands of door knockers who led our election effort into hundreds of thousands of socialist cadre, involved in agitation and organisation alongside workers and tenants in their communities, using collective action to take on landlords and bosses, and spreading the kind of class struggle mentality and politics that we can build a movement out of.

The question, as ever, is what exactly all these nice words mean. This has to be the topic of further discussion, all of which which should be based on detailed and specific proposals for action.

The next few years are going to be tough. Our chances of getting through them sucessfully, however, are much higher if we remember one simple rule: they fuck with one of us, they fuck with all of us.

-

As Keir Milburn has argued (via Stuart Hall), age is one of the vital modalities through which this class divide is lived. Milburn, K. (2018) Generation Left ↩

-

On the other hand, the Tories listed their few canvassing sessions on a series of small and barely-formatted regional web pages. Evidence of Tory canvassing was very thin on the ground. ↩

-

These numbers need to be treated with some skepticism - however. People often misreport their past voting behaviour, and Ian Allinson has argued that this Ashcroft data substantially overestimated the votes of the minor parties in 2017. ↩

-

Engels, F. (1895) introduction to Marx’s The Class Struggles in France: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1850/class-struggles-france/intro.htm ↩

author

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1)

read next