Working-class internationalism and the aid worker

by

Navid Somani

August 16, 2018

Featured in The Worker and The Union (#3)

On the weakness of organised labour in the international aid sector

inquiry

Working-class internationalism and the aid worker

by

Navid Somani

/

Aug. 16, 2018

in

The Worker and The Union

(#3)

On the weakness of organised labour in the international aid sector

In my near ten years working in the aid sector, for seven different INGOs (international non-governmental organisation), only one has formally recognised a trade union. This anomaly was largely down to the fact that said INGO’s stated aim was to improve labour rights in global supply chains, thereby making the hypocrisy of ignoring workers organising in its own workplace too on the nose. Otherwise, my experience has been of a workplace dominated by technocrats, just as hostile to the idea of collective action on the part of citizens in the global south as they are to their own colleagues organising for improvements in working conditions locally. These experiences are symbolic of an aid sector that has been captured by a neoliberal agenda, and whilst this phenomenon has been well researched by scholars, the literature rarely touches on the role of the workplace in ensuring that this dogma remains largely unchallenged from within. Here I want to explore this, and speak specifically to the challenges that not only prevent aid workers from improving the condition of their own labour, but also from speaking out against the free market philosophy that underpins the economic injustice they are seeking to address.

My sole experience of working at an organisation which recognised a trade union not only wasn’t replicated elsewhere, but conversely, I found plenty of hostility to the very idea of worker representation. One previous employer, who claimed to be working to realise the rights of children globally, took thinly veiled punitive actions against workers after they failed to gain either voluntary or statutory recognition of a union for purposes of collective bargaining. What was particularly egregious about the actions of this charity is that it was not enough to do this once, but when rumours emerged about a second attempt to unionise, it took similar action again to permanently extinguish any hopes on the part of workers. Putting aside the hypocrisy of such actions on the part of an organisation engaged in issues of injustice, the fact of it speaks to the precariousness inherent in the aid sector at large.

A few organisations can sustain a large body of permanent staff, usually because of large endowments (e.g. Mastercard Foundation), or regular membership fees (e.g. UN agencies). But most are recipients of donor funding, usually disbursed for specific time-bound projects, with detailed budgets, which include the salaries of staff and length of their contracts. This creates a situation where short-term staff contracts are the norm, and use of external consultants is frequent. Those consultancies, whilst not comparable to the material conditions of those working in the gig economy, are analogous in that workers in the aid sector are increasingly setting themselves up as independent consultants, thereby losing those benefits (sick pay, paid leave, pensions etc) normally associated with employment. For those who persevere on short-term staff contracts, they are expected to endure the stress that goes with insecure employment, whilst also delivering against project objectives, regularly travelling to difficult environments abroad, and working on emotionally draining issues. More perversely, I’ve witnessed staff having to submit fundraising applications not only for the sake of securing another project for the charity, but also in the hope that said project will provide for their own salary for another year or two. Despite these difficulties, staff welfare is rarely a concern, and instead, employers use this insecurity to maintain the balance of power in favour of them. This manifested itself in the most tragic of circumstances earlier this year, when Gaëtan Mootoo, a veteran human rights activist at Amnesty International, took his own life citing the stress of his work life and the lack of assistance from his employer.

All of this is being further compounded by neoliberal “innovations” in the funding environment, such as the payment by results (PBR) model championed by the UK government’s Department for International Development. Also used elsewhere in the public sector, PBR essentially only disburses funds to implementing organisations after they have been able to demonstrate independently verifiable results. Apart from the problems this creates in forcing organisations to be too timid in the problems they seek to address, they also create an additional source of stress for staff working on such contracts, with their employment potentially at risk. Professor Robert Chambers, an academic at the Institute of Development studies, highlighted this issue in his blog post on PBR, when he spoke about the plight of “a participatory organisation with an excellent track record which is being bankrupted through one of these contracts: the senior management have had no remuneration for six months.”

How the INGO workplace came to be a place of insecurity is inextricably tied to the aid sector’s role in the demobilisation of radical politics in the global south. This started in the post-war period, when charities and international institutions became instrumentalised to serve a depoliticising, liberal agenda. Marxist thinker, Antonio Gramsci, describes this process as manufacturing consent, whereby civil society, unlike political society, is the key arena in which capitalists (or otherwise) achieve cultural and ideological hegemony. Not only did this take place with the capture of key civic institutions internationally, but also domestically, with Margaret Thatcher being particularly successful in establishing such hegemony, shifting notions of “common sense” to the right, as described by the late sociologist, Stuart Hall. Her greatest achievement was the birth of New Labour, who fervently picked up her neoliberal project where she left off. Led by a leader with delusions of grandeur in Tony Blair, they revived international aid as a key tool in manufacturing consent for a global liberal technocracy, which also complemented their more violent attempts to shape the world through military intervention. In that regard, they picked a sector particularly suited for such a project, with INGOs being described a places where “transnational networks of like-minded actors link together through a convergence of interest, outlook and technique, thereby allowing certain ideas to become dominant, through a process of so-called “consensus.””1 This was seen in the near-universal adoption of the Millennium Development Goals, and their successor the Sustainable Development Goals, but most literally in the World’s Banks neoliberal articulation of what development should look like, un-ironically named “The Washington Consensus”.

Given this, it will be no surprise that throughout my time working in international development, the workplace, particularly senior management, has been dominated by Blairites. I mean this not only in an ideological sense, but literally, with figures associated with the New Labour project coming to dominate the international aid sector. Many not only saw it as a proving ground for their technocratic policies before entering politics, but as the Labour Party has moved further left in the last few years, it increasingly serves as a refuge from a world they no longer understand. The obvious example to point to would be the appointment of Blair’s failed successor David Miliband to the position of CEO of the global refugee charity the International Rescue Committee.

Closer to home, the story of Save the Children (STC) UK is one that is particularly illustrative of how a workplace swarming with third way obsessives, can have toxic consequences. STC’s reputation in my sector is infamous, with almost everyone knowing someone who endured an awful time working there. I recall one colleague returning to the charity where I worked, having only left six months earlier to go to work at STC in a more senior role. In their brief time there, they raised a grievance against a colleague, ultimately deciding to take a demotion, just to get out of the organisation. It was no surprise then, when a colleague shared an article from the Daily Mail in 2015, covering the resignation of STC’s chief strategist, Brendan Cox, after several allegations had been made by female staff of inappropriate behaviour. The charity’s CEO, Justin Forsyth, also resigned around the same time, after “unsuitable and thoughtless” comments to three young female members of staff, the fact of which only emerged years later. Both just happen to have also been senior advisors to former Prime Ministers Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The story gained very little traction outside the Mail at the time, with many dismissing the story in the context of the Mail’s general hostility to helping foreigners, whether here or abroad. This was until 2018, when Cox, now most known as the widow of Jo Cox, the Labour MP killed by a right-wing extremist during EU referendum, was caught up in the #metoo movement. Back when he resigned, he strenuously denied the allegations made against him, but when they re-emerged, he partially admitted his “mistakes”, and stepped down from various charities he had been involved with (being praised by MPs from Labour’s right for doing so, including Jess Phillips, who conversely didn’t extend such generosity when implying British Asians had a misogyny problem). Stories also began to emerge of the toxic working environment that Forsyth and Cox presided over, where bullying was the norm and those making complaints were dismissed as “moaners”. The Blairites had not only brought their “third way” politics to the charity’s programme, but also the abrasive Alastair Campbell-inspired managerial style synonymous with the New Labour years.

Where do we go from here?

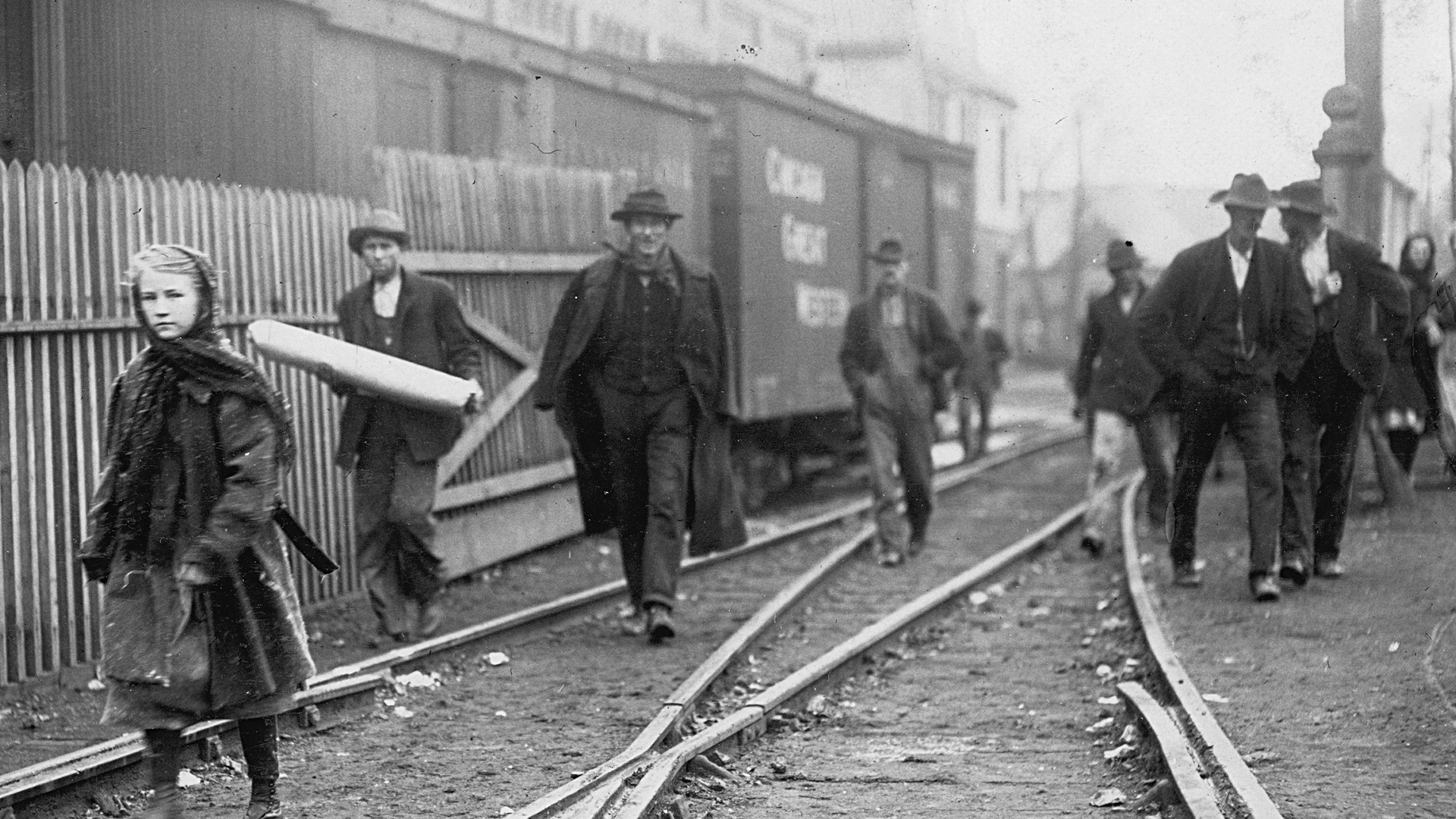

The recent abuse scandal in the aid sector shows how the power imbalances inherent in the aid sector are most acutely experienced by those in the global south. Those imbalances are based on a model of aid which deliberately creates a permanent relation of dependency of poor nations on rich ones, echoing the critiques Marx made of globalisation more than a century ago.

In that context, then, would workers at INGOs joining trade unions en masse, in a sector with so much vested interest in upholding the status quo, do much to make a difference for those in the global south? Yes, at least in the short- to medium-term.

In Marx’s opening address at the first meeting of the International Working Men’s Association in 1864, he made an appeal for a working class internationalism. He cited how the solidarity shown by British cotton pickers had prevented Prime Minister Palmerston from intervening in the American civil war to maintain the slave trade. This is the inspiration that aid workers should have in mind when seeking to unionise - organising not only to reduce your own precarity, but also to shift the balance of power towards those in the global south. Examples of such radical action are few, but some parallels can be drawn with those staff who organised at Save the Children to force management to apologise for grotesquely awarding Tony Blair with a “global legacy” prize.

A better organised aid sector could be even more courageous, pushing back against the neoliberal policies of their donor-hungry employers in favour of something more equitable. I recall an incident when an employer objected to the workers discussing a proposal from the charity to take funding for a private sector education initiative in Africa. Clearly fearful that the bright and articulate workers would not endorse such an intervention, thereby endangering a potential source of revenue, the employer successfully prevented the meeting from taking place. Eventually the project didn’t go ahead for unrelated reasons, but had there been structures in place for the workers to organise, they not only could have met, but also worked together to stop the project from proceeding as far as it did.

On numerous other occasions, I’ve seen staff at INGOs object to a myriad of proposals from their employer - expressly in solidarity with people in the global south - on issues of gender, safeguarding, or the ethics of particular donors. Except for a few tokenistic staff consultations, workers voices were mainly ignored in determining the policy of the charities on these issues – because they could be.

At some point, the aid sector will need to have a reckoning. I still believe that in the absence of more radical action, aid workers can be and often are an ameliorative force in relieving some of the worst impacts of neoliberalism. There will come a time, though, where the entire existence of the sector will need to be questioned if it comes into conflict with a genuine opportunity to create a more just economic and social system globally. In the meantime, we as aid workers also need to take up the challenge of being that radical force within our workplaces, organising to turn the aid sector from a neoliberal racket to one where working class internationalism is reborn.

-

Jones, P. W. (2006). Education, poverty and the World Bank. Rotterdam: Sense. ↩

Featured in The Worker and The Union (#3)

author

Navid Somani

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next