Automation and the Future of Work

theory

Automation and the Future of Work

by

Aaron Benanav

/

Nov. 24, 2020

An interview with Aaron Benanav

Jamie is an editor of Notes from Below

Aaron Benanav is a researcher at Humboldt University of Berlin and the author of Automation and the Future of Work

Could you tell us about the new book?

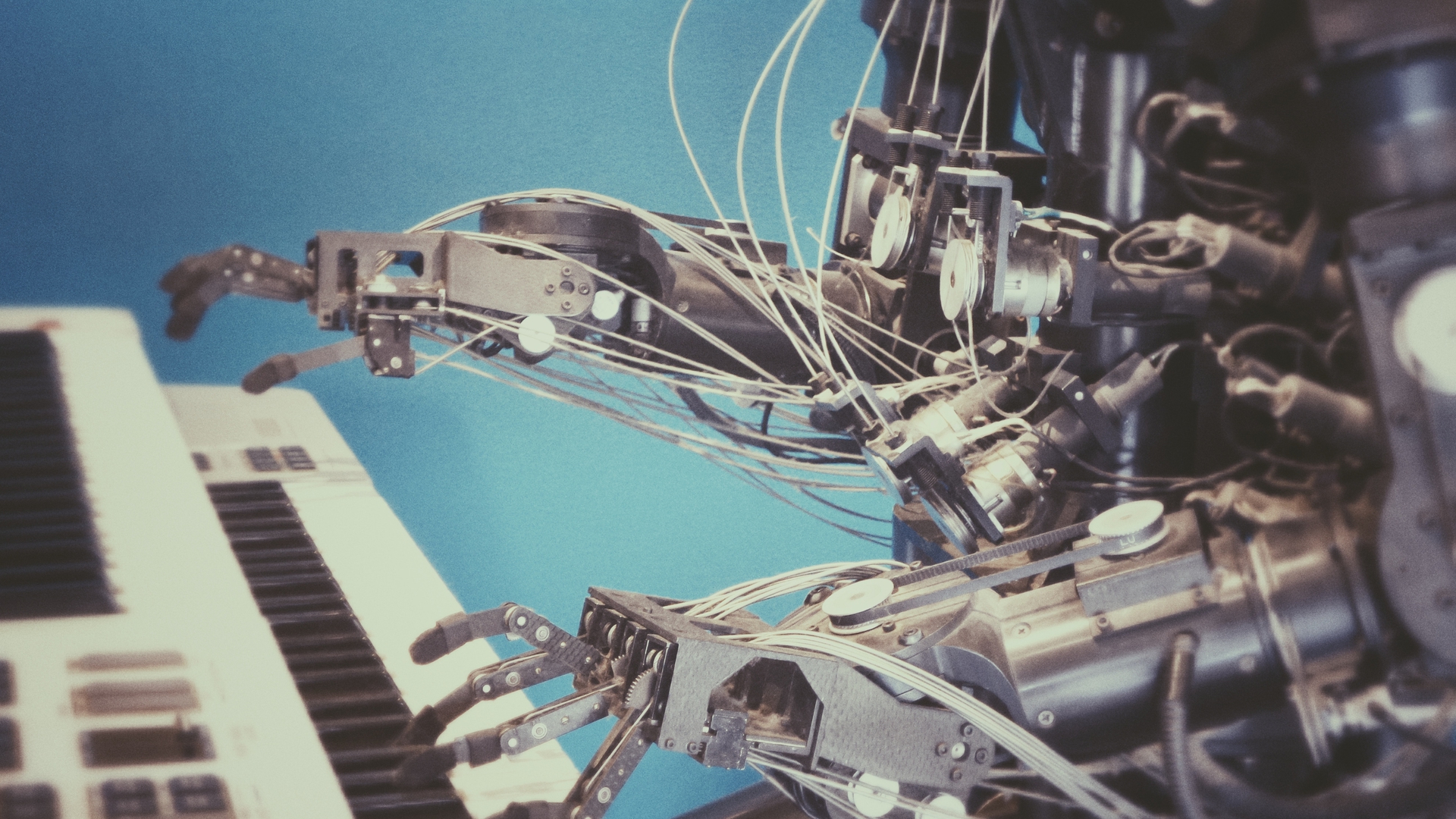

The book is about the resurgence of an interest in workplace automation. There’s a lot of tech news about automation, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. What I’m particularly interested in is how this hype around workplace automation has given rise to a broader social theory, which argues that the tendency towards automation is driving social conflicts in advanced capitalist societies and across the world. They say: look around you, workers are being replaced more and more by intelligent machines; in the future, most labor will be obsolete. There are already economists who are critical of that framework, such as Robert Gordon and David Autor. I expand on their work in my book. But economists talking about these issues tend to downplay the severity of global labour underdemand—which is very real—and which the automation theorists are trying both to explain and to resolve.

I should note here parenthetically that, in my book, I try to shift the conversation away from use of the unemployment rate as a measure of low labor demand. Instead I use that more general term—a “low demand for labour”—which isn’t exactly exciting but is a crucial corrective. Over the past 40 years, states have removed many of workers’ labor market protections (or, in the global South, have failed to implement such protections) forcing workers who are newly entering the labor market or who have lost their jobs to find work as quickly as possible. Even when they do get jobs—hence are no longer technically unemployed—most workers worldwide are still subject to a severe loss of autonomy, or workplace bargaining power, associated with an economy-wide low labor demand.

The evidence for this is everything the automation theorists cite: stagnant wages, falling labor shares of income, rising inequality, and a proliferation of “bad jobs.” I end up arguing that 45 years of economic stagnation and welfare state retrenchment, rather than workplace automation, are the forces making for a severe global jobs problem. It is a problem that long predates recent high tech innovations. My book explains why the automation theorists’ story about low labor demand is incorrect but stresses the need to imagine similarly transformative solutions to the world’s labor underutilization problem. I say something like: here’s how we can get a world like the one the automation theorists want, without needing automation—by reorganizing and redistributing the work that remains to be done.

What effect to you think this has on the kinds of movements and the kinds of politics that are emerging in the wake of a pandemic? In the UK, we’re facing a huge, huge wave of redundancies and so there is an even greater tightening of the number of jobs that are available.

We clearly we live in a time of experimentation. I draw from traditions within the left—broadly associated with the idea that social change must come from below—that say: we need to actually look to workers to understand how they’re responding to these changes in the world of work, and to support workers struggles where they are happening. One thing we’ve seen, especially in the United States and around the world, is that you see a lot of workers struggling outside of the workplace, because they feel too weak there.

People feel like they can’t make gains in the workplace, so they’re participating in broader social movements. Look at the US, where we had the largest social movement, possibly in US history, taking place in response to the police murder of George Floyd. There is a potential for cross-current development between social movements and new and emergent workers struggles. Any realistic appraisal of where the left’s power could come from, or where potentials for social transformation could come from, are going to have to look to these two sites and understand how struggling in an era of low demand for labour has forced a lot of people to struggle outside of their workplace.

One of the projects we’re embarking on in Notes from Below is trying to understand how class composition has shifted in the UK. I think one of the weaknesses of the left is that there are some of these larger macro analyses of trends that are happening, but little on workers’ actual experiences. While you’re right to point out that some of them are assumed around automation, what do you make of this challenge of connecting broad analysis to concrete experience?

I do focus on the macro trends, but that’s because I think we really do need to make sense of those trends in order to gain a better picture of how the working class, its struggles, and its orientation towards an emancipatory future are all changing over time. In that regard, the end of the book discusses resurgent class and social struggles since the 2008 crisis, which have been growing and intensifying worldwide, albeit unevenly. I point out that these are no longer the struggles of an industrializing workforce, fighting over the shape of an industrial society that is in the process of coming into being. Instead, our struggles are taking place in an era of deindustrialization, in a period of slowing economic growth and austerity. In their struggles, workers are trying to figure out what sort of emancipatory pathways remain open.

There are, I think, broadly two ways to think about what emancipation could look like, that relate to workers’ shifting relationships to the production process. First, there is an old demand, with a long history, particularly in socialism-from-below traditions: the demand for workplace control and workers’ autonomy. Here, one might think of teachers or nurses, who see themselves as performing an essential and meaningful social labour, which could be done much better if workers had more of a say in how their work was done and with what resources. By contrast, the second demand is to be free of one’s job, to be able to quit and do something else, outside or beyond work, which isn’t captured by terms such as “rest” or “leisure.” Here, one might think of many workers in other parts of the service sector—including in the growing platform economy—who see their jobs as little more than a means to the end of survival. For these workers, life is elsewhere. It would be interesting to have a map, not only of what workers are doing, but also of the extent to which they imagine freedom as a transformation of their workplace, or as no longer having to work there.

People within emancipatory politics are going to have to think about these two visions of emancipation and the way that they relate to work and the possibilities within them. The inspiring vision of the future will likely be one that speaks to both experiences: on the one hand, transforming meaningful work to be done better—with greater worker (and consumer) control—and, on the other hand, working less. There is a connection, although not a direct one, between these different concrete experiences of work and the sorts of places people find it easier or more meaningful to engage in struggle and conflict. My sense is that engaging with utopian literature, even the misguided techno-utopianism of the automation literature, is worthwhile as a way to build a stronger emancipatory movement.

This is an important point and I think one that is often missed with the “short-cut-ism” of some politics focused on automation: how do we take up that idea of utopianism in practice?

I saw an article on the Notes from Below website about rebuilding emancipatory politics. There was a line in there that reminded me a lot of something that I say in my book, which is that our situation is actually a lot more like the mid to late 19th century than any other more recent moment. We’re very far from having the power to transform society. People with ideas about how to transform society are cut off from the broader working class movements, which are themselves mostly reduced to fending off attacks from a powerful capitalist class. What was crucial, at that time, was to bring these two strands together—the socialist ideal and the labor struggle. People were able to fight for small changes, against great odds, because they saw themselves as part of a much larger project. Even though they knew that the struggles they were involved in required major efforts but did not produce dramatic change, they saw them as necessary steps towards a more beautiful tomorrow.

My sense is that today, people lack such an inspiring and motivating vision. For a while now, we’ve felt that we have no future—in a world of endless neoliberal reform, resurgent ethnonationalism, and onrushing climate catastrophe—what we’re heading towards feels like a catastrophe. I’m not saying that these intuitions are wrong—that things will actually turn out to be bread and roses—but to even have a chance at change, we need to recover a utopian impulse and imbue social and labor movements, which are the forces that could actually bring about major social change, with that impulse. “Fully automated luxury communism” and the “Green (New) Deal” are attempts to do this, and even though I am critical of both, both are attempts to begin to envision a future. This will be absolutely essential to changing the way we act within struggles emerging “from below”.

Having that visions is a big challenge to the left or organisers today. I noticed that you mentioned Star Trek in the introduction to the book, so I wonder if you could speak to how culture can help shape our understanding of these alternative utopian futures. And also, you don’t say which series of Star Trek?

A teacher who ended up having a big effect on me is Manu Saadia, who later went on to write Trekonomics. He encouraged me to take classes with Moishe Postone, a Marxist theorist who had a major influence on my intellectual trajectory. In terms of the series, it’s definitely The Next Generation, but it could also be Deep Space Nine.

At the risk of going off onto a tangent here (and the best is Deep Space Nine) how does broader science fiction help with making sense of this utopian politics?

Utopian literature helps us imagine broad changes in social life, without demanding that these broad changes be made coherent. For example, a new technology might render drudgery unnecessary, and a science fiction author, like Iain M. Banks in his Culture series, explores the consequences of that change for humanity. How exactly human needs and wants are named and met in those books is black-boxed. We never find out exactly how the Culture works. The same can be said of the world depicted in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home. In any case, I find that science fiction imaginings are an important counterweight to more realistic depictions of socialist societies, which, no matter how imaginative their construction, end up describing a society that looks like a nicer American suburb, where the goal of life is have a good time at work, and then come home, crack open a beer, tinker with a car in the garage, and watch TV. Is that all people would do with their freedom? I think not. We have to dream bigger, much bigger, than “hobbies.”

An interesting feature of utopian texts is that they typically begin after the action of social change has already taken place. It’s much rarer to have utopian literature that depicts that transformation itself—how it happens. I would really recommend two very different visions that do that imaginative work. The first is William Morris’s wonderful News from Nowhere. It has a beautiful account of how society changes, through an amazing description of a strike that transforms itself into a true social revolution. The other text, from a similar milieu, is Peter Kropotkin’s The Conquest of Bread, which is in my view a neglected utopian text, in a lot of ways. A big difference between Morris and Kropotkin is that the former tries to imagine a world where work has really become the fulfilment of life, whereas the latter imagines what people would do once the working day had been significantly shortened.

Further afield, there are science fiction and utopian texts that try to imagine social change unfolding on a much longer time scale, like Lord of Light by Roger Zelazny. It’s an amazing depiction of a social revolution that unfolds over 300 years, with major battles—often lost by the emancipatory side—that produce dramatic changes in social organization over long periods of time. So I’m on the lookout for not just models, but visions. I would like to have a left that’s more interested in imagining and winning the future, in different ways.

So how do you think these can help connect to our experiences of struggles today?

I’ve been quoting this line from Alice in Wonderland, that my friend, the computer programmer, Björn Westergard has said to me a few times: “When you don’t know where you’re going, any road will get you there.” Having some shared vision of positive social change—or plural, visions—helps us identify which of the small steps we could take might lead us somewhere different. We need to imbue our struggles with a positive conception of a different world, whether in our workplaces, out in the streets, in organising against landlords or fighting against the onslaught of austerity.

Automation and the Future of Work is out now with Verso.

author

Aaron Benanav (@abenanav)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Automation From An Engineer's Perspective

by

Evelyn Ting

/

June 19, 2018